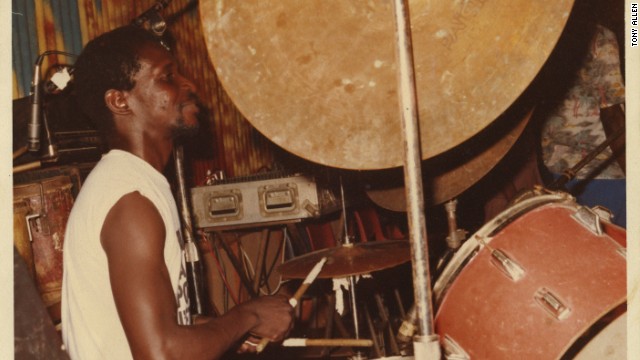

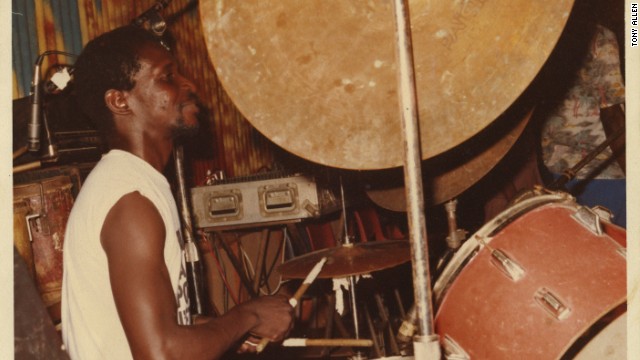

First of all, drummers are going to love this book. With so few autobiographies of drummers in print, the publication of

Tony Allen: An Autobiography of the Master Drummer of Afrobeat is a cause for celebration. Co-author Michael Veal, author of

Fela: The Life and Times of a Musical Icon and an accomplished musician himself, brings to life the rhythm and emotional timbre of

Tony Allen's

speaking voice and the complex story of this singular,

Lagos-born-now-expatriate musician in a first-person narrative that

takes the reader through a particularly transformative time in West

Africa's post-colonial history. Most importantly, the book is a hell of a

lot of fun to read, although Allen's first-hand accounts of his

struggles with shamanistic bandleader and Nigeria's adopted "black

president"

Fela Anikulapo-Kuti will piss

off any musician who has had to fight to get paid for playing a gig. And

Allen's chillingly matter-of-fact recollection of the aftermath of the

1977 military raid on Fela's "Kalakuta Republic" compound, a raid that

involved beatings, rape, mutilation, and nearly burning the compound to

the ground, is truly terrifying.

Swinging Like Hell! Afrobeat, a musical genre

that Veal describes as Nigeria's "sonic signature," was born out of

Allen's mastery of what he describes as "a fusion of beats and

patterns," including highlife, rumba, mambo, waltz-time, traditional

music from Nigeria and Ghana, American R&B and funk and, not

surprisingly, jazz. On Allen's first U.S. tour with Fela's band Koola

Lobitos, a band that would be renamed Africa 70 upon its return to

Nigeria, Allen heard and met drummer

Frank Butler, who played drums with such musicians as

Duke Ellington,

Miles Davis, and

John Coltrane.

Allen cites the drumming techniques he learned directly from Butler as

"the final piece of the puzzle that just made everything catch on fire."

And catch on fire it did. In his vivid description of Allen's

drumming on the track "Fefe Naa Efe" from Fela and Africa 70's 1973

album

Gentlemen, Veal writes: "Like the great jazz drummers,

(Allen) keeps a steady conversation with the other instruments,

particularly the soloists...Like a great boxer, he knows when to jab

with his bass drum in order to punctuate a soloist's line, when to

momentarily scatter and reconsolidate the flow with a hi-hat flourish,

when to stoke the tension by laying deeply into the groove, and when to

break and restart that tension by interjecting a crackling snare accent

on the downbeat."

The book not only reveals Allen's methodical,

years-long development of a new way to play the drum kit and propel

Fela's compositional and political vision, it also shows Allen never

stopped developing his technique post-Fela and continues to bring "the

vitality of Yoruba artistic creativity" into new and innovative creative

contexts. Allen negotiated the "world beat" market of the 1980s and 90s

and experimented, like many African musicians recorded during those

years, with heavily electronic and dub production techniques. In recent

years, Allen has recorded and performed with American, French, and

British musicians from genres that may seem light years away from his

highlife roots. He saves some of his highest praise in the book for

Damon Albarn, formerly the lead singer and bandleader of the wildly

popular British band Blur and who has collaborated with Allen on several

projects. "The way Damon came into my life," says Allen, "it was kind

of like it had been written...not only did this guy make a big

difference in my career, but we are also very good friends."

After

many years of being underpaid and under appreciated for his

innovations, Allen is currently enjoying a creative renaissance. One of

the most moving passages in the book comes toward the end when Allen,

now in his 70s, describes how busy he is "touring all over" Europe and

what drives his creative work ethic. "I still want to play something

impossible," Allen writes, "something that I never played before."

allaboutjazz.com

'I still want to play something impossible': Meet Afrobeat king Tony Allen

The first thing he asked was 'Are you the one who said that you are

the best drummer in this country?' I laughed and told him, 'I never said

so.' He asked me if I could play jazz and I said yes. He asked me if I

could take solos and I said yes again."

That's how Tony Allen

details his first ever encounter with Fela Kuti back in the mid-1960s, a

meeting that was destined to trigger an explosive sonic collaboration

that a few years later gave birth to the

blistering Afrobeat sound -- arguably the most exciting period in the history of popular West African music.

This anecdote, and many more others, are featured in the

newly released autobiography of Allen,

the iconic Nigerian drummer who's left an indelible stamp on the

history of world music with his distinctive style and pioneering

grooves. Brian Eno has hailed Allen as the "greatest living drummer."

Co-written with Michael

E. Veal, "Tony Allen: An Autobiography of the Master Drummer of

Afrobeat" follows Allen's life from his early days growing up in the

heart of Lagos Island, though his struggling first steps as a badly paid

freelance musician, the meeting with Fela and the heights of their

"Africa 70" band, to his departure from the group and his relocation to

Paris in the mid 1980s.

Master drummer

Born in Lagos in 1940 to a

Nigerian father and a Ghanaian mother, Allen was the oldest of six

children. His first gig came in late 1950s when he started playing clefs

in a highlife group called "The Cool Cats," before taking over the

band's rhythm section.

From then on, Allen went

on to hone his self-taught drumming skills by dipping into different

styles as a member of several other Lagos bands -- including "Agu Norris

and the Heatwaves," "The Paradise Melody Angels" and "The Western

Toppers."

In 1964, Allen met up

with Fela and his career took a different, more exciting path. Over the

next 15 years, Allen would be the rhythmic engine for the Nigerian

multi-instrumentalist and political rights activist, first for the

highlife-jazz outfit "Koola Lobitos" and then for the seminal "Africa

70" group.

It was after the band

returned from a 10-month stay in the United States in 1969 that Allen

created the potent drumming concept of Afrobeat, fusing the different

beats and patterns he'd heard while growing up with the new techniques

he'd mastered as a professional drummer -- everything from highlife and

traditional Nigerian music to Western jazz, funk and R&B.

"I was looking for

something," Allen says, from Paris, where he is currently based. "I

wanted to be myself," he adds. "I played like everybody already but

there was no point in continuing doing that because I'd be bored

completely."

Allen, the only member

of Fela's band allowed to compose his own parts, could famously drum in a

different time signature with each of his four limbs. Driven by his

fluid and steady drumming, Africa 70 went on to record a string of

highly successful and politically charged albums, which turned Fela into

a huge musical and countercultural icon in Nigeria and abroad.

But it was onstage where the full force of Afrobeat's intoxicating sound and the talents of Fela and Allen really shone through.

"With me and Fela, it's a

question of telepathy," Allen says of the musical closeness he enjoyed

with "Africa 70's" firebrand leader.

"That is why I was able

to stick around this guy for 15 years -- you know, I never did that with

anyone before; the maximum time I stayed in a band was one year," adds

Allen.

"Since I met him I knew

that this guy had something, this is the type of challenge I needed ... I

just believed that I am meeting a genius and it's great to work with a

genius."

Life after Fela

This deep appreciation

of Fela's musical brilliance oozes through the pages of Allen's

autobiography. But the narrative is also filled with wrangles over

payments and recognition. In the end, Allen says it was not the ongoing

pay disputes but the increasingly volatile situation around Fela's

political activism that led to Allen leaving the group in 1978 -- events

like the army attack on Fela's compound in 1977.

"The only thing that

happened was that it became a package of madness," Allen says. "I stood

it for a while too, I was inside it -- I had been arrested, I had to

submit myself because he is like my brother."

Allen's departure left a

big void in the heart of the Afrobeat sound. Fela, who replaced his

polyrhythmic sideman with four drummers during live performances, once

said that "there would be no Afrobeat without Tony Allen." The two

remained friends until Fela's death in 1997.

After leaving "Africa 70," Allen went on to form his own bands in Nigeria before relocating to Paris in 1985.

Since then, he's

released several well-received albums. A musician committed to

innovation, he's joined forces with an eclectic roster of both African

and international musicians over the years-- including Damon Albarn,

King Sunny Ade and Jimi Tenor.

Today, at the age of 73, Allen still remains as active as ever.

"I don't see the end of

exploring," says Allen, who is currently working on a new album. It's a

sentiment echoed in his final remarks in the book.

"I still challenge

myself every time with my playing," Allen writes. "I still want to play

something impossible, something I never played before."