Unfortunately cannot find any information ...

Nov 23, 2018

Nov 15, 2018

Vaudou Game - Otodi

Through thick layers of dust, the console was vibrating still, impatient to be turned on and spurt out the sound so unique to analog. That sound is what Peter Solo and his band Vaudou Game came to seek out. The original vibrations of Lomé’s sound, resonating within the studio space, an undercurrent pulsing within the walls, the floor, the entire atmosphere. A presence at once electrical and mystical, sourced through the amps that had never really gone cold, despite the deep sleep that they had been forced into. In taking over the studio’s 3000 square feet, enough to house a full orchestra, Vaudou Game had the space necessary to conjure the spirits of voodoo, those very spirits who watch over men and nature, and with whom Peter converses every day.

For the most authentic of frequencies to fully imbibe this third album, Peter Solo entrusted the rhythmic section to a Togolese bass and drum duo, putting the groove in the expert hands of those versed in feeling and a type of musicianship that you can’t learn in any school. This was also a way to put OTODI on the path of a more heavily hued funk sound- the backbone of which maintains flexibility and agility when moving over to highlife, straightens out when enhanced with frequent guest Roger Damawuzan’s James Brown type screams, and softens when making the way for soulful strings. Snaking and undulating when a chorus of Togolese women takes over, guiding it towards a slow, hypnotic trance.

Up until now, Vaudou Game had maintained their connection to Togo from their base in France. This time, recording the entire album in Lomé at OTODI with local musicians, Peter Solo drew the voodoo fluid directly from the source, once again using only Togolese scales to make his guitar sing, his strings acting as channels between listeners and deities…

hotcasarecords.com

Labels:

Vaudou Game

Nov 14, 2018

Ebo Taylor - Yen Ara

Conquering lion of Highlife Music, Ebo Taylor has truly seen it all and done it all. The 83-year-old Saltpond based musician, songwriter and composer is just about to begin another world tour as he promotes his latest body of work. The 9-track album titled, Yen Ara, released via Mr Bongo in march of 2018, sees him translating various knowledge bases encoded in traditional Fanti music in contemporary Ghanaian highlife as well as experimenting with certain new rhythmic forms through signature, horn-dominated composition. The album, eagerly anticipated and brilliantly received so far is another stroke of Ebo Taylor’s genius.

At a very comfortable 41 minutes, the album begins with Poverty No Good, introduced by a solemn and choral admonition of poverty. The song, one of which Ebo Taylor composed and arranged, then roars into life with the rolling drum loops metronomed by a muffled conga and brazen horns sections, bridged by Ebo Taylor’s Pidgin English verse on the impossible nature of living with poverty. The charged tempo of the song counters the patient melody he creates with his voice and sets a tone of blending and mix which is consistent through the tape.

The next few songs, however, slope towards more polarized dance-friendly highlife and afrobeats. Mumundey for instance, feature this rousing war-like call and response refrain, sandwiched between rousing trumpet solos, one of Ebo Taylor’s well-known fatality moves. Track 3, Krumandey is more of late 70s disco and funk with a feel good atmosphere that slaps the rhythms onto listeners. The entire song rests on the strong shoulders of this punchy electrifying horns sections that season the vocals of Ebo Taylor’s son, Henry Taylor, whose strong voice rises above the cauldron of bliss on this song. It easily one of the stand out cuts on this tape.

Abenkwan Pucha, however, is the crown jewel of this album as it perfectly syncs the two critical phases of Ebo Taylor’s composition: i.e. the more traditional vocal highlife, brewed from Palmwine Music, to his jazzy funk phase which has become his signature in the African music pantheon. The song has this freshly ground feeling of warmth with yet again, the kinetic and tender horns section, as well as Tony Allen style drum pattern as Ebo Taylor in his aged, raspy voice appears to be using palm nut soup as some grand metaphor.

For casual or first time listeners, this project is by far a huge pool of highlife bliss to dive into as it partially traces the contours of this very Ghanaian genre, showing how the sound has evolved from the palm wine days, through funk and disco to the experimental, electro-based, burger highlife days. It also exhibits Ebo Taylor’s brilliance as a composer. The entire project feels well round with no gagged melodies and unessential phrases taking away from the overall sounds. Ebo Taylor along with the Saltpond City Band and producer Justin Adams, brilliantly engineered soundscapes for the narratives, with the trusted horn section as the pillar upon which the entire sonic architecture is arranged.

However, this is same compositional level, is where the magic that elevates this body of work happens. Despite having a uniquely homogenous sounds, certainly elements do stick out. A considerable chunk of the composition on this album have already appeared on previous bodies on work. In an interview with Afropop Worldwide, Ebo Taylor does admit to repurposing these classics and playing around with certain compositional element to make them fresh for today’s world. In the same interview, he also mentions the another chunk of the album came from songs sung by various Asafo troupes. “We try to get it into a danceable form, while keeping its history”, Ebo Taylor says in the interview. The Asafo, a group of warriors in Akan communities are one of the sub-set of Ghanaian culture that instrumentalize song. Ebo Taylor, shamelessly borrows some of their melodies and rhythms in composing this album. By so doing, he also documents and records this custom that seems to be fading away.

Yen Ara represent one of the final iterations on a quest to perfection. By dedicating his life to the music, Ebo Taylor has worked religiously to achieve what could be a near perfect sound. Not only does he achieve this on this album but he also pays homage to Fanti culture and how the communal use of music to lubricate daily chores is the main ingredient in his sonic composition. Through Yen Ara, the Asafo tradition of music remains alive, although it should make you pause and think about the current state of communal Ghanaian musical culture.

dandano.org

- - - -

The horns breaking through the beautifully composed opening track is akin to the sunshine through a cloudy day. The effervescent jingles of the music is irresistible and blissful. Drenched in both hyper-energy and mellow grooves, Ebo taylor and his Saltpond City Band delivered one of his most albums in his catalogue.

The 81 year old indefatigable musician is a known pioneering figure within the afrobeat circles and highlife music in general.

”Yen Ara”, his latest project is a live recorded album produced by Justin Adams. The live recording session took place at the Electric Monkey Studio in Amsterdam. The themes on the album bothers on tradition, culture, life and heritage.

Here’s a track-by-track breakdown of the album.

Poverty No Good

A call and response song with a pidgin title. It carries a triumphant horn section with adowa rhythms bubbling across the song. ‘In this man’s world, life’s is how you make it, no 1 wants to be poor’; his old voice echoes before the Fante phrase ‘ohia be y3 ya (poverty will be painful) shut shop on the first verse.

Ebo Taylor sings in both Fante, English and pidgin. The poignant message in this song is: don’t be poor; strive for riches.

Mumudey Mumudey

Mumudey Mumudey is quintessentially a jama tune. It breathes the potency of Osode-a traditional highlife folk music popular amongst fishermen and carries enchanting grooves.

The song opens with a famous phrase made popular by Gyedu Blay on ‘Simigwa Do’. Ebo Taylor compares himself with the handsome and dapper character-who rocks good clothes and sunglasses- with himself and his family members. The afrobeat elements are as boisterous as ever.

Krumandey

From the lyrics, one is left thinking ‘Krumandey’ as a type of dance. He urges all ‘little children to play the game’. Perhaps it’s an old game popular during his young years. It’s sound like a plea to go back to picking some of the traditions of old as well.

Aboa Kyirbin

The uptempo tone of the three previous songs wanes, paving the way for this mid-tempo tune. Soulful horns open the song. The vocals are gentle and soft. This song talks of the need to cast away a spell with Aboa Kyirbin which he describes as a worm eating creature.

The song, like many highlife tunes carry a philosophical depth. Aboa Kyiribin refers to a type of poisonous snake. Employed as a metaphor to reference how the deeds of people is harming this country, Ebo Taylor calls for the snake that is now feeding on worms (a very strange happening) to be sacrificed to cast away the ills bedevilling the country.

This point is validated by these lyrics (translated from Fante): fellow citizens, we need to sacrifice aboa kyirbi (snake) to cast away a spell. This call elicit a response from his singers: ‘my country Ghana drenched in tears. ‘’Abro Kyirbin’’ qualifies as both a political and social call for the right actions to be taken to ameliorate the sufferings we have contributed in creating. Unlike other songs that plays to end, this ends abruptly.

Mind Your Own Business

This song picks up from the up-tempo vibrations of the first three records. You hear the emotive guitar works of Uncle Taylor who, after a minute of renditions of danceable rhythms, repeatedly sings ‘don’t let my business be your business because ‘I’m too strong for you. So please don’t judge me’.

He’s preaching about ignoring criticism and living your life: ‘All which you think is my downfall, but blessings dey drop like rainfall/music is my weapon and I’m doing what I want’. The guitar chords after the second verse and the horn section is as gentle as it can ever get.

The simple sing along chorus reminds me of another beautiful composition by now defunct Marriot International Band in the mid-90s with same title.

Ankona’m

Song title translate from Fante to English as ‘lonely person’. Derived from a popular wise saying, he highlights the plight of the lonely person in this world as the lines of the song reveal: ‘I’m a lonely man, who’ll help or speak for me when I’m in trouble’. The lonely man doesn’t have friends or family to support him and mostly the society shuns him.

‘’Ankona’m’’ has a jazzy- highlife feel. His singing evokes a tone of sombreness. The instrumentation accompanying this song is mellow and swingy. The guitar riffs from Ebo Taylor whizzes across the soft percussion drums with grace. The pain in his voice can’t be missed.

Abenkwan Puchaa

Now, this song celebrates one of the most prominent soups on the menu list in many Ghanaian homes. ‘Abenkwan’ refers to palm nut soup. On the song, he describes a mouth-watering palm soup with beans, mushroom, akrantie, crab, snail, okro as essentials. This song validates the ‘fante-ness’ of Ebo Taylor- he loves good food.

Yen Ara

The mini-climax of the beat at the beginning; the bassline that reverbs across momentarily; the long solo horn section permeating across the serenity of the drums without any disturbance. All these coalesce to hand “Yen Ara”, the album title its grace.

“Yen Ara” (We) is an ode to his hometown of Cape Coast-a historic town in the Central Region with the crab as a symbol. It is said that, the 17 clans of Cape Coast (known locally as Oguaa) won a battle against thousands of men- a reference to their victories against the Ashantis during the colonial era.

It’s a song that reflect the history and formidability of the people of Oguaa. Yen Ara is the shortest song on the album. It plays for just 3 minutes 11 seconds.

Abaa Yaa

‘’Abaa Yaa, come here. She has a University education. Unbeknownst, she can’t speak Fante’’. These are the opening lines on Uncle Taylor’s closing song “Abaa Yaa”. He pivots two scenarios to capture what he thinks is an erosion of our tradition and culture, including our language. He cites how a lady-Auntie Lizzy- finished basic school yet can’t speak Fante (her local dialect). Abaa Yaa is actually a remake of an old tune with same title, found on his ”Life Stories: Highlife and Afrobeat Classics 1973-1980” release.

Contrasting these scenarios with the action of a proper Englishman who drinks tea with fried plantain balls. For Ebo Taylor, we should safeguard our culture and identity. This theme has been a favourite of his and seem to be borrowed from his song ‘Ohy3 Atare Gyan’.

“Yen Ara” is a well-conceived and excellently executed album with variants of musical influences he has been part of since he began some six decades ago. It shares elements of highlife, afrobeat, jazz and swings within the scope of mellow, mid-tempo and high tempo rhythmic detonations.

His style of blending his mother tongue of Fante with pidgin and English is indicative of his desire to keep it both Ghanaian and African as well as global.

The performance by his band, Saltond City Band- a handpicked group of musicians including two of his sons is as entrancing as the overall work on the album.

culartblog.wordpress.com

Labels:

Ebo Taylor

Oct 16, 2018

The unstoppable renaissance of Afrobeat

(Translated with googletranslate from German magazine WELT)

He was pastor's son, polygamist, pothead and the inventor of a novel style of music: with his Afrobeat Fela Kuti reconciled Africa and the West - at least on the dance floor. A tribute.

He would never die, said Fela Kuti. He had his middle name Ransome, a slave name, exchanged for Anikulapo, and this name means that he carries the death in his bag, so he could not harm him. When Fela Kuti died on August 3, 1997, at the age of 58, of AIDS, he was actually far more alive than in previous years. More than a million people populated the streets when his body was laid out in the Lagos stadium. No one went to work for two days, and for once there were hardly any crimes. Even the gangsters and petty criminals who loved Fela Kuti so much should all have been busy dealing with their grief.

There was the loss of a great musician, composer and rebel. In the early 1970s, Kuti invented Afrobeat, a synthesis of highlife, jazz and funk, and released more than 50 albums during his career. He headed two of the most influential bands in African pop music with Africa '70 and Egypt '80; He maintained a community in the middle of Lagos for his musicians, the family and all who wanted to be there, a commune he called the Kalakuta Republic and declared it an autonomous state territory.The amazing thing is that his fame has continued to grow steadily ever since. Jay-Z and Will Smith have produced this with a number of Tony's excellent Broadway musical "Fela!". Last year saw the wonderful documentary "Finding Fela!" By Academy Award winner Alex Gibney. And the New York label Knitting Factory makes Kutis music accessible again in all dosage forms. Questlove of the Roots, Ginger Baker and most recently Brian Eno have curated magnificent vinyl boxes. The label is currently releasing Fela Kuti's albums as new prints, also on vinyl.

He was Nigeria's public enemy number one and has been arrested more than a hundred times. After releasing his hit "Zombie" in 1976, which was not friendly with the military dictatorship, a thousand soldiers stormed Kalakuta, threw his old mother out of the first-floor window and set fire to the buildings.

Months later, when the mother died as a result of her injuries, he carried her coffin to the official residence of Nigerian President Olusegun Obasanjo and released the album "Coffin For Head Of State." But Kuti was also an avid stoner, smoking nonstop bags of gigantic proportions, as well as a zealous polygamist who married 27 women in a ceremony in 1978, which is said to have earned him a temporary entry in the Guinness Book of Records.

You could think of Fela Kuti as a particularly peculiar mix of Duke Ellington, James Brown, Bob Marley, Nelson Mandela, and Hugh Hefner, and would not even half-do it justice.

The legend of Lagos

Kuti is born on October 15, 1938 as Olufela Olusun Oludotun Ransome-Kuti in Abeokuta as the fourth of five children of a Nigerian middle-class family. His father Israel Oludotun Ransome-Kuti is a Protestant pastor, his mother Funmilayo a well-known political activist, winner of the International Lenin Peace Prize and first woman of Nigeria with a driver's license.

At 19 Kuti is sent to London to study medicine or law, but ends up at the conservatory and studies composition, trumpet and piano. When searching for accommodation, he experiences racism ("no blacks, no dogs"), gets to know the music of Miles Davis and Dizzy Gillespie, founds his first band with the Koola Lobitos. In 1963 he returns to Lagos, but the high-life jazz of his Koola Lobitos does not really want to ignite the audience there, because jazz takes the high life momentum and people want to dance above all else. The necessary inspiration comes in the form of the records of James Brown, but only a ten-month trip with the entire band to America completes the music of Fela Kuti.

Because his new girlfriend, Black Panther activist Sandra Smith, introduces him to the writings of Malcolm X and Eldridge Cleaver, Kuti begins to develop African consciousness beyond Africa, and uploads his pieces with political content. As Smith, who now calls herself Sandra Iszadore, recalled in an interview, he previously sang songs about soup, among other things. If he had continued to sing about food, his career would probably have been calmer, but great artists are not only the product of their talents, but also the product of their time - and the times were not good.

Songs like circles

After Nigeria was released from independence in 1960 by the British Parliament, it experienced from 1966 an almost absurd sequence of military dictatorships. Constantly, new generals came to power, while the oil boom gave the country a wealth of which the people, thanks to its elite, had practically nothing. Nigeria was marked by corruption, mismanagement, poverty, and violence, and Fela Kuti felt called to take care of it.

But you can not imagine his protest songs as "Tell me where the flowers are" -song, which asks about the meaning of wars and is supported by the desire to be tolerated, please. Kuti was not an intermediary. He attacked. And so that everyone understood his concerns, he sang them in Pidgin English, which was common in the whole Anglo-African language area.

A kuti composition lasts about 18 minutes on average, but can easily be twice as long. It usually starts with a theme that is set by a few instruments, gradually adding other building blocks, with a single instrument never playing the full melody, but only a small part, resulting in the songs constantly moving but the whole thing remains in a tight rhythmic corset. The brass breaks in, the sound gets bigger, and if you think the song might be over, it's not even started yet.

At some point, half of the song is almost over, Kuti also turns on. He declares more than he sings, the chorus speaks up, there is a back and forth of voices, then again the brass, the guitars and the beat, which goes on and on. When the American singer Jim James of the band My Morning Jacket was interviewed about Kuti, he said that he always had to think about the setting of circles in this music. It turns and turns, and you do not want it to stop.

What a stage band, better than the Beatles!

The attraction of this music to other artists was enormous, especially on western ones. Almost every night Kuti played with his band Africa '70 in his nightclub "African Shrine" in Lagos and received among others James Brown. Stevie Wonder also came by and also Paul McCartney. He had fled to Lagos because he wanted to record the album "Band On The Run" with the Wings.

McCartney still remembers the evening at Shrine. In a video interview that can be seen on YouTube, he says, "It was the best live band I've ever seen." There, he also heard his favorite kuti song that he never found a recording of but he still remembers the reef. McCartney sits down at the keyboard and starts playing. It is the song "Why Black Man Dey Suffer".

Without ever having heard it since then, Paul McCartney still has it in his ear forty years later.

Originally published in German @welt.de

Labels:

...articles,

Fela Kuti

Oct 1, 2018

Hoodna Orchestra - NO A.C

Hoodna Orchestra, also known H.A.O, is an Israeli Afrobeat band from the south part of Tel-Aviv, formed in 2013. Inspired by the humming and clanging of carpentry and metal workshops.

Originally conceived as a traditional Afrobeat group, H.A.O quickly developed a far spikier sound, often played faster and more emphatically than many of their contemporaries. They have also proven adept at broadening their sound by incorporating influences from a variety of other genres. H.A.O.’s rousing live shows quickly attracted an enthusiastic following.

Debut EP: “No A.C.”

en.fbmc.co.il

Labels:

Hoodna Afrobeat Orchestra

Sep 28, 2018

" Commandments" by The Seven Ups

Melbourne's 7-piece afro-groove combo, The Seven Ups, are releasing their third full length album, Commandments, and are throwing a launch party at Howler to celebrate.

Building on the bands

Funk and Afrobeat influences, the new album pushes the boundaries by

adding elements of deep psych and fuzz rock. Whilst maintaining high

energy grooves, the new tracks venture to the meaner and darker edges of

the genre.

Labels:

The Seven Ups

Sep 26, 2018

Fela Kuti: Musical Genius And Activist

Sunday 18 October was the final day of Felabration; a weeklong annual

musical jamboree to celebrate the life, times, music, and ideology of

the phenomenon called Fela. Born Olufela Olusegun Oludotun Ransome-Kuti

on 15 October 1938, this scion of the popular Ransome-Kuti family of

Abeokuta was a singer/songwriter, composer, and multi-instrumentalist.

They gained worldwide popularity as a foremost Nigerian family. The

family has put the country on the world map, being as popular for their

musical heritage, as they are for their political activism. Fela’s

musical genius was never in doubt, and even in death, eighteen years on;

his great body of work is still being studied, enjoyed, and reworked,

finding a presence in every corner of the globe. An off Broadway

production of Fela Anikulapo- Kuti’s life titled Fela, and a full length documentary titled Finding Fela have even been produced.

A cursory look at his family tree reveals that Fela was not an

accident, in his case the apple did not fall far from the proverbial

tree. This son and grandson of Anglican priests (popularly known as the

musical priests) simply carried on the family tradition. The story

begins with the Reverend Canon Josiah Jesse Ransome-Kuti; an Anglican

priest responsible for composing many of the hymns sung in the Anglican

Church, both within and outside Nigeria. He recorded a series of songs

in the Yoruba tongue for the Zonophone record label in London. JJ it was

who took the name Ransome, in honour of the missionary who converted

him.

Next comes the Reverend Israel Oludotun Ransome-Kuti, a priest like

his father, he was an educationist who went to become the Principal of

Abeokuta Grammar School, and also president of the Nigerian Union of

Teachers. His wife Funmilayo was an activist, and women’s rights

campaigner, who received the Lenin peace prize in 1970. Mrs. Funmilayo

Kuti’s marriage into the family brought political activism into the Kuti

family. The couple had four children; Olikoye, Bekolari, Fela, and

Dolupo. Olikoye; a renowned doctor, and Professor was at various times

Minister of Health, and Deputy Director-General of the World Health

Organisation, Beko also became a doctor, and was Secretary-General of

the Nigerian Medical Association.

As was usual with the offspring of the upper middle class Nigerian

families of his day, Fela was a young colonial Nigerian male music

graduate of an English university, playing a fusion of Jazz and highlife

music charting a course for himself. In 1969, he went to Los Angeles on

tour with his band, and met Sandra Smith, now Izsadore. Smith belonged

to the Black Panther Party and the Nation of Islam, and was overjoyed to

meet Fela as she hoped to learn more about African history from him. To

her surprise and dismay, she discovered that he knew next to nothing

about the history of Africa, thereafter she took him under her wing and

opened his eyes to the vista of African consciousness, and the black

power movement. They became lovers, and by the time Fela returned to

Nigeria nine months later, his psyche, and music had changed. He left

Nigeria a colonial relic, but returned a proud black man.

As radical as he was talented, Fela discarded the family name

Ransome, saying it was a “Slave name”, taking on Anikulapo, which means

“He who has death in his pocket”. He also turned his back on the

Anglican, nay Christian faith of his fore bearers, preferring to return

to his African roots. For the rest of his life, Fela would practice the

African traditional religion. He entered the Guinness book of records

for wedding twenty seven women in one day. The wedding was blessed by

the chief ifa priest of Lagos. Fela was often vilified for

licentiousness, but as his son, Seun puts it, “Fela was just a very open

person, and lived his life as he wished. Many men were guilty of the

things he did, they only tried to hide theirs. Many men have children

showing up after they are dead and gone. Quite a number of people from

all works of life smoke Marijuana, but prefer to hide it.”

Continuing the family tradition, albeit in his own way; Fela trained

his eldest son in the age old way of the apprentice learning at the feet

of the master. Residents of the John Olugbo axis of Ikeja, Lagos in the

early eighties remember a father teaching his young son to play the

keyboard; he would play a note, and ask the lad to do the same. It was

no joke, only the already famous Fela taking the time to teach his heir

the rudiments of the family business; unknowingly preparing him for the

international stage and stardom. Although his father had a degree in

music, Femi’s success and subsequent superstardom without a music degree

are testimony to the genius of the afrobeat icon. Speaking to the

Nation Femi said, “When my first international hit album broke, Fela

asked me, ‘ Do you now see what I have been trying to teach you all

these years? You can now feed yourself through music’. And I agreed.”

Funmilayo Ransome-Kuti was the matriarch of the clan, and was a great

source of inspiration to her large brood. Her granddaughter; Yeni Kuti

vividly captures this when she said, “My grandmother is my role model.

She inspired me a lot. She once teased Femi about his laziness in

rehearsing his saxophone, wondering how he could succeed as a musician

without rigorously rehearsing. Femi never missed daily rehearsal ever

since.” Fela was a very hardworking musician as visitors to the shrine

can testify. During his lifetime, Fela was known to play his saxophone

into the wee hours of the morning; meticulously blowing his sax day in

day in day out, year in year out. This acerbic tongued Egba woman was

also known to be self-sacrificing as she was part of the group that

campaigned for the abolition of women paying tax at the time. Why? Women

were already overstretched, supporting their husbands in taking care of

their families. As the wife of a middle class reverend gentleman, and

educationist, she was financially comfortable enough to have buried her

head in the sand, but chose to fight on the side of the oppressed.

A chip off the old block, Fela’s music was often critical of the

different corrupt, and profligate Nigerian regimes; whether military or

civilian. He churned out hit after hit; songs as aesthetically pleasing,

entertaining, and thought provoking as they were full of acidic wit.

Songs like Unknown Soldier, Soldier go soldier come, and Zombie

ruled the airwaves during the military era, oftentimes causing him to

be brutally beaten, his house and properties burned, in addition to

being thrown behind bars. He quickly got used to going to prison. As his

daughter Yeni puts it, “It was a challenging time for us because when

we left home for school in the morning, we did not know if we would meet

him on our return, or even when next we would see him”.

Dede Mabiaku paints a more graphic picture of the ire Fela’s songs

drew from previous governments when he said, “How many people even know

that the last time Kalakuta was burned that they beat the merciless

bombastic element out of everyone there, to the extent that his mother

was thrown out of the window, that is true, to the extent that they even

tore somebody’s stomach open, and he held his guts in with his hands.

Nobody told you about that, they wanted to jab Fela with a bayonet, and

somebody flung one of the boys on top of him, so the bayonet pierced the

guy’s stomach, and his guts came out. Let me paint a picture for you,

they held his guts in hands to the hospital (the guy is still alive

today). But that was not the issue, they stripped Fela naked, flogged

him silly, broke his leg. He was bleeding all over profusely from being

caned with whips, down to his privy . . . .”

Surprisingly, with their political activism, and patriotism one would

have thought that one or the other member of the family would vie for

political office. But as Yeni puts it, “As long as the political terrain

of Nigeria remains as it currently is, I can never play politics.”She

goes on to say, “I would never want to do anything to disgrace the name

of my family.”

A down to earth and humble lot, they made friends with people from

different strata of the social divide. Charles Oputa, a much younger

artist to Fela has this to say about Fela, “When my friend; Tina

Onwudiwe graciously paid two years rent for an apartment in the Gbagada

area of Lagos for me, in a bid to encourage my movement to Lagos from

Oguta, I was overjoyed.” Can you guess the superstar who visited him the

day of his housewarming party? Yes, Fela. Charlie Boy continues, “When

he showed up at my apartment that day. I was so shocked, because I

usually visited him at the shrine, Fela was not known to visit

musicians, and I felt honored to be the only one he visited.” That was

not all, Oputa quipped, “Fela stayed the whole day, chatting and goofing

around. I finally had to tell him, ‘Fela, a beg I wan sleep’ before he

left late that night.”

Are the Kuti’s a lucky family, or is there something in their gene

pool responsible for their success? What character traits stood them in

good stead to continually conquer whatever stage they found themselves?

What reasons can be adduced for their success? As Seun Kuti puts it,

“Our direct fore bearers were so accomplished that we have to work hard

to live up to their standards.” Speaking about the man Fela, Dede

Mabiaku; his protégé has this to say about his late mentor, “He was a

perfectionist. He was one who believed that if something had to be

done, it had to be done the right way. Fela scored his songs by himself,

he scored notes for everyone and the instruments; for the guitar, the

drums, the horns, the tenor, the alto sax, and gave everybody. So you

had to rehearse it to his dictates”.

Tracing directly from JJ Ransome Kuti, to Reverend Oludotun Ransome-

Kuti and beyond, the musical line directly continues through the late

Fela, to his sons Femi, and Seun who have continued the family tradition

on the world stage; the former with his Positive Force Band, and the

latter as the helmsman of Fela’s band. Femi’s son; Made is the fifth

generation of the musical family, and is presently in the UK studying

music at his grandfather’s alma mater.

Like him or hate him, Fela was not a man you could ignore. When he

died of an AIDS related complaint in 1997, Lagos state stood still to

say goodbye to the man who bestrode the Nigerian musical, and

sociopolitical terrain like a colossus. More than a million people

comprising fans, friends, well-wishers, and even critics turned up for

his funeral at the old shrine premises; Nigeria had never seen anything

like it, and probably never will.

thenationonlineng.net

Labels:

...articles,

Fela Kuti

Sep 24, 2018

Polyrhythmics - Libra Stripes

Literally and figuratively, funk is a four-letter word. Through a process of reiteration and misappropriation, funk emerged from radically creative African-American empowerment and has since been diluted to its goofiest signifiers. Funk, in most quarters, is considered frivolous.

Yes, the adepts—James Brown, George Clinton, Sly Stone, Prince—are proponents of having a really good time. But they’re also dead serious about fun as a means to an end: Free your mind and your ass will follow. The destination is liberation.

I say all this because Libra Stripes is 40 minutes of real-deal, straight-up, hardcore funk. No platform shoes, star-shaped glasses or Afro wigs here. No retro-soul vocals or pat exhortations to fall back on, no venerable front-person singing a redemption song to earn your empathy. Not that there’s anything wrong with that stuff—but this is something else. Polyrhythmics make dense, driving, instrumental dance music, living and pulsing and sweating, made by eight stellar musicians who are all business, and their business is making you move.

The members of Polyrthymics are part of a loose-knit scene of musicians who come together in and around the Sea Monster in Wallingford. This homey little place is Ground Zero for hard funk in Seattle; go when there’s music on and you will dance. The prime instigator is guitarist Ben Bloom, who also plays in Rippin’ Chicken and Unsinkable Heavies. But where those groups ply funk forms that are buoyant and bouncy or sinuous and jazzy, his Polyrhythmics are as heavy as a wrecking ball. They don’t fuck around. They play out frequently and have recorded a half-dozen or so highly collectible vinyl 45s for a couple of different U.S. labels. Libra Stripes brings to bear all their kinetic energy in a sustained, focused studio albums for the first time, and it smokes.

What you hear here is polyglot funk, postmodern and well-studied but not without unhinged moments. Various tongues are deployed in service of ambiance—Fela’s woozy Hammond organ, Joe Bataan’s conga-driven percussion, Bobbi Humphrey-esque flute, Family Stone-style horns, dubby analog effects, hip-hop-ish syncopation. Ambiance, in turn, serves groove. Combined, the two create an all-consuming sound.

Whether it’s the sauntering, Afro-Latin swagger of “Moon Cabbage,” the ’70s cop-show theme-song tension of “Bobo” or the Southern-fried soul of “Skin the Fat,” the music is simultaneously referential and wholly original. There is, after all, a long, star-studded legacy of funk, and these guys are wise to keep in touch with their forebears, both to provide technical foundation and to understand where and when to stray from established templates.

There’s nothing experimental or out-of-bounds here; that would feel like trying. Instead there’s only doing. Embodiment. Of the funk, and all the freedom it brings.

Yes, the adepts—James Brown, George Clinton, Sly Stone, Prince—are proponents of having a really good time. But they’re also dead serious about fun as a means to an end: Free your mind and your ass will follow. The destination is liberation.

I say all this because Libra Stripes is 40 minutes of real-deal, straight-up, hardcore funk. No platform shoes, star-shaped glasses or Afro wigs here. No retro-soul vocals or pat exhortations to fall back on, no venerable front-person singing a redemption song to earn your empathy. Not that there’s anything wrong with that stuff—but this is something else. Polyrhythmics make dense, driving, instrumental dance music, living and pulsing and sweating, made by eight stellar musicians who are all business, and their business is making you move.

The members of Polyrthymics are part of a loose-knit scene of musicians who come together in and around the Sea Monster in Wallingford. This homey little place is Ground Zero for hard funk in Seattle; go when there’s music on and you will dance. The prime instigator is guitarist Ben Bloom, who also plays in Rippin’ Chicken and Unsinkable Heavies. But where those groups ply funk forms that are buoyant and bouncy or sinuous and jazzy, his Polyrhythmics are as heavy as a wrecking ball. They don’t fuck around. They play out frequently and have recorded a half-dozen or so highly collectible vinyl 45s for a couple of different U.S. labels. Libra Stripes brings to bear all their kinetic energy in a sustained, focused studio albums for the first time, and it smokes.

What you hear here is polyglot funk, postmodern and well-studied but not without unhinged moments. Various tongues are deployed in service of ambiance—Fela’s woozy Hammond organ, Joe Bataan’s conga-driven percussion, Bobbi Humphrey-esque flute, Family Stone-style horns, dubby analog effects, hip-hop-ish syncopation. Ambiance, in turn, serves groove. Combined, the two create an all-consuming sound.

Whether it’s the sauntering, Afro-Latin swagger of “Moon Cabbage,” the ’70s cop-show theme-song tension of “Bobo” or the Southern-fried soul of “Skin the Fat,” the music is simultaneously referential and wholly original. There is, after all, a long, star-studded legacy of funk, and these guys are wise to keep in touch with their forebears, both to provide technical foundation and to understand where and when to stray from established templates.

There’s nothing experimental or out-of-bounds here; that would feel like trying. Instead there’s only doing. Embodiment. Of the funk, and all the freedom it brings.

- - -

I can only imagine what it’s going to be like November 2nd at The Crocodile Café when the Polyrhythmics release their new record, Libra Stripes. So much dancing – the corner of 2nd and Blanchard might register on the Richter.

The night, which will also feature the hip-swaying Picoso, will celebrate the new record, one of funky depth and force. But the songs on the album might be even better heard live! They have such a fine mix of low-end and bright horns, one can’t help but want to hear the music loud and on stage.

I have long been a fan of Polyrhythmics because they aim to get their audiences to dance, and dance often. It seems the band’s top priority. Upon listening to their newest album, the first thing I noticed was the backbone beat. Jason Gray on bass is subtle but voluminous and plays with impeccable timing and taste. Each song seems to be built in some way around him. Ben Bloom, front man and architect of Polyrhythmics, accompanies the rest of the band without self-indulgence. His eclectic guitar sneaks around the tracks, all while keeping precise time.

Maybe my favorite song on the 9-track Libra Stripes is “Moon Cabbage”. It almost sounds like a Beastie Boys beat. There is also an outer-space quality to it, while still being rooted in Gray’s stone-solid baselines. There are no vocals on the entire album, but we aren’t left wanting them either. On “Moon Cabbage” the horns provide the melody.

At The Crocodile for the album release show, the room, assuredly, will be packed. People, in the otherwise chilly November night, will be dressed in fine clothing, some even scantily! The energy will be loose and joyful. Moods will be brightened. Bodies will move. And the people will want more.

I can only imagine what it’s going to be like November 2nd at The Crocodile Café when the Polyrhythmics release their new record, Libra Stripes. So much dancing – the corner of 2nd and Blanchard might register on the Richter.

The night, which will also feature the hip-swaying Picoso, will celebrate the new record, one of funky depth and force. But the songs on the album might be even better heard live! They have such a fine mix of low-end and bright horns, one can’t help but want to hear the music loud and on stage.

I have long been a fan of Polyrhythmics because they aim to get their audiences to dance, and dance often. It seems the band’s top priority. Upon listening to their newest album, the first thing I noticed was the backbone beat. Jason Gray on bass is subtle but voluminous and plays with impeccable timing and taste. Each song seems to be built in some way around him. Ben Bloom, front man and architect of Polyrhythmics, accompanies the rest of the band without self-indulgence. His eclectic guitar sneaks around the tracks, all while keeping precise time.

Maybe my favorite song on the 9-track Libra Stripes is “Moon Cabbage”. It almost sounds like a Beastie Boys beat. There is also an outer-space quality to it, while still being rooted in Gray’s stone-solid baselines. There are no vocals on the entire album, but we aren’t left wanting them either. On “Moon Cabbage” the horns provide the melody.

At The Crocodile for the album release show, the room, assuredly, will be packed. People, in the otherwise chilly November night, will be dressed in fine clothing, some even scantily! The energy will be loose and joyful. Moods will be brightened. Bodies will move. And the people will want more.

- - -

Polyrhythmics began as an experiment amongst like-minded musicians in the Pacific Northwest. Having been seasoned players in various soul, jazz and rock collectives, Ben Bloom and Grant Schroff sought to make an EP of original afrobeat and syncopated funk songs. Recording led to performing, then touring; that handful of songs soon grew to sixty; a Canadian crate digger took notice. Following up their 2011 debut full-length, Labrador, Polyrhythmics return with their dance-oriented second LP, Libra Stripes, on Calgary's Kept Records. Whether it's the smooth guitar and ride cymbals that make up the groove of "Snake in the Grass," or the hyper horns stabs of "Bobo," Polyrhythmics have perfected the art of getting people moving, and the results are wonderful. If instrumental music isn't your thing, then yes, you should probably steer clear of this album, but folks who want to dance to an EDM-alternative will be well served by Libra Stripes. The art of digging has long been focused on finding that rare old gem, but Polyrhythmics prove that funk need not have a time stamp.

Tracklist

1. Libra Stripes

2. Pupusa Strut

3. Moon Cabbage

4. Chingador

5. Snake In The Grass

6. Bobo

7. Skin The Fat

8. Retrobotic

Labels:

Polyrhythmics

Sep 19, 2018

Oghene Kologbo & World Squad - Music No Get Enemy

Oghene Kologbo, born in Warri (Nigeria) in 1958, has been an integral

member of the legendary Fela Kuti's Africa 70 for the whole life of the

band. This made his tight tenor guitar playing be a fundamental presence

on all the masterpiece records that defined the sound of Afrobeat and

brought him to play with people of the likes of James Brown, Stevie

Wonder, Lester Bowie, Paul McCartney, to name a few. After leaving Lagos

for good with other members of Fela's band, Kologbo lived in Berlin

from 1978 and since then toured with King Sunny Ade, Tony Allen and

Brenda Fosse, among many others. He also founded a number of successful

bands such as Roots Anabo and projects with Adé Bantu and Xavier Naidoo.

Sep 18, 2018

Zamrock: Mike Nyoni & Born Free - My Own Thing

Zambian guitarist and singer/songwriter Mike Nyoni’s music is Zamrock

only because he came of age during the country’s rock revolution. His

preferred wah-wah to fuzz guitar, James Brown to Jimi Hendrix. His 70s

recordings – often politically charged, and ranging from despondent to

exuberant – are amongst the funkiest on the African continent. He was

also one of the only Zamrock musicians to see his music

contemporaneously issued in Europe.

This anthology collates works from his three 70s LPs – his first, with the Born Free band, and his two solo albums Kawalala and I Can’t Understand You – and presents a singular Zambian musician on par with celebrated artists Rikki Ililonga, Keith Mlevhu and Paul Ngozi.

- - -

The latest release

in Now-Again's deluxe Reserve Edition series: the first ever anthology

of Zamrock musician Mike Nyoni's funky, psych-rock and folkloric 1970s

recordings spread over 2 CDs. Zambian guitarist and singer/songwriter

Mike Nyoni's music is Zamrock only because he came of age during the

country's rock revolution. His preferred wah-wah to fuzz guitar, James

Brown to Jimi Hendrix. His 70s recordings -- often politically charged

and ranging from despondent to exuberant -- are amongst the funkiest on

the African continent. He was also one of the only Zamrock musicians to

see his music contemporaneously issued in Europe. This anthology

collates works from his three 70s LPs -- his first, with the Born Free

band, and his two solo albums Kawalala and I Can't Understand You

-- and presents a singular Zambian musician on par with celebrated

artists Rikki Ililonga, Keith Mlevhu and Paul Ngozi. The package also

features an extensive, photo-filled booklet contains an overview of the

Zamrock scene and Nyoni's story.

forcedexposure.com

- - -

Mike Nyoni and Born Free - My Own Thing - Now-Again Reserve

This 2 disc on revered label Now-Again's Reserve subscription series

continues the label's fascination with the Zamrock scene and sound.

It's obviously a labour of love for label boss, Egon, and the care and

attention lavished on the package serves to do justice to the music

presented.

The context given by the accompanying literature gives a great insight

to the geopolitical landscape of the era, Zambia's position on this

landscape, and the journey between now and then for both the country and

the artefacts of this scene.

Focusing on Mike Nyoni, this compilation distils three albums of music, both solo and with the Born Free band.

The sound is much tighter and cleaner than you'd expect based on the

previous releases in the series. The guitar work is clear and melodic,

utilising a blues/funk scratch rhythmic interplayed with a pickier lead

to great effect across the first disc. A hermetic rhythm section drives

the tunes with fierce power, and steady, rather than frenetic pace, the

quoted influence of New Orleans funk easy to hear.

No washing fuzz or reverb, no wig out moments, just tight arrangements

overlaid on strutting grooves. Nyoni's voice, whether singing in English

or languages local to his enforcedly nomadic history, oozes sincerity,

both on the personal and political songs. Given the tumultuous

environment he wrote in, it's unsurprising that political themes

resonated with such emotional depth.

Disc one ends with Chikwati Chata, where wah is applied to a

recognisably Southern African guitar groove and lead melody, and drum

pattern that will be familiar to anyone well versed in the last decade's

worth of Afro-insert-genre-here re-issues and re-works.

Sounds like a pivotal point?

Disc 2 is much more Nyoni's work with (The) Born Free band. Essentially

their one album, with some singles from prior to this, the production is

less sharp, the band looser, and the arrangements more open to

freestyle sections.

The influence of Hendrix is more obvious - the instrumental Mad Man

being a prime example of trio playing more to sections than strict

structures. This is aligned more closely to the inspiration that

Woodstock era 'classic rock'' had on the Zamrock sound overall, and

documents the beginnings of an artist finding his place within a

movement, before the further self-definition outlined on the previous

disc.

Overall this is a great collection of works presented with an

educational package worthy of inclusion on any official syllabus that

you could align the outcomes to. The socio-political climate of the

country, the region, the post-colonial upheaval, a nation's leader

trying to exert independence and support the rights of Africans within

their own countries to self-rule, the conflicts and hardships this

caused for their people, and how a generation of musicians interpreted

and expressed this through a lens of optimistic post-hippie ideals. Rock

transported from the civil rights US to an independence seeking African

country, funk born of this and forged with peacenik ideas, this is a

story worth telling, and worth your time hearing.

Labels:

Mike Nyoni And Born Free

Sep 17, 2018

African Scream Contest Vol.2 - Benin 1963-1980 (by analogafrica)

A great compilation can open the gate to another world. Who knew that some of the most exciting Afro-funk records of all time were actually made in the small West African country of Benin? Once Analog Africa released the first African Scream Contest in 2008, the proof was there for all to hear, gut-busting yelps, lethally welldrilled horn sections and irresistibly insistent rhythms added up to a record that took you into its own space with the same electrifying sureness as any favourite blues or soul or funk or punk sampler you might care to mention.

Ten years on, intrepid crate-digger Samy Ben Redjeb unveils a new treasuretrove of Vodoun-inspired Afrobeat heavy funk crossover greatness. Right from the laceratingly raw guitar fanfare which kicks off Les Sympathics’ pile-driving opener, it’s clear that African Scream Contest II is going to be every bit as joyous a voyage of discovery as its predecessor. And just as you’re trying to get off the canvas after this one-punch knock out, an irresistible Afro-ska romp with a more than subliminal echo of the Batman theme puts you right back there. Ignace De Souza and the Melody Aces’ “Asaw Fofor" would’ve been a killer instrumental but once you’ve factored in the improbably-rich-to-the-point-of-being-Nat-King-Cole-influenced lead vocal, it’s a total revelation.

The screaming does not stop there, in fact it’s only just beginning. But the strange thing about African Scream Contest II’s celebration of unfettered Beninese creativity is that it would not have been possible without the assistance of a musician who had been trained by the Russian secret services to "search and destroy" enemies of the country’s (then) Marxist-Leninist president Mathieu Kerekou.

Already familiar to fans of the first African Scream Contest as a mainstay of ruthlessly disciplined military band Les Volcans de la Capitale, Lokonon André vanished in a cloud of dust at Ben Redjeb’s behest with a list of names and some petrol money, only to return a few days later having miraculously tracked down every single name he’d been given. The source of this Afrobeat bounty-hunter’s impressive people-finding skills - his training with the KGB - highlights the tension between encroaching authoritarian politics and fearless expressions of personal creative freedom which is the back-story of so much great African music of the 60s and 70s. Happily, in this instance, Lokonon was tracking the artists down to offer them licensing deals, rather than to arrest them.

Where some purveyors of vintage African sounds seem to be strip-mining the continent’s musical heritage with no less rapacious intent than the mining companies and colonial authorities who previously extracted its mineral wealth, Samy Ben Redjeb’s determination to track this amazing music to its human sources pays huge karmic dividends.

Like every other Analog Africa release, African Scream Contest II is illuminated by meticulously researched text and effortlessly fashion-forward photography supplied by the artists themselves. Looming large - alongside Lokonon André - in the cast of biopic-worthy characters to emerge from this seductive tropical miasma is visionary space-nerd Bernard Dohounso, who laid the foundations for Benin’s vinyl predominance by importing and assembling the turntables that would play the products of his Bond villain-acronymed pressing plant SATEL, a factory that would revolutionise the music industry in the whole region.

The scene documented here couldn’t have been born anywhere else but in the Benin Republic , and the prime reason for that is Vodoun. It’s one of the world’s most complex religions, involving the worship of some 250 divinities, where each divinity has its own specific set of rhythms, and the bands introduced on the African Scream Contest series and other compilations from that country were no less diverse than that army of different Gods. At once restless pioneers and masters of the art of modernising their own folklore, the mystic sound of Vodoun was their prime source of inspiration.

One especially irascible Vodoun-adept was Antoine Dougbe, who styled himself “The devil’s prime minister” while turning ancestral rhythms into satanically alluring modern beats. As Orchestre Poly-Rythmo songwriter Pynasco has observed sagely, “Evil is not elsewhere, evil extends into the house”. And African Scream Contest II is a gloriously cinematic road-trip through an undiscovered realm of music lore whose familiarity is every bit as thrilling as its otherness.

analogafrica

Five songs into African Scream Contest 2 comes one of the greatest recorded screams I’ve ever heard.The Picoby Band D’Abomey have just begun to play “Mé Adomina,” a track built around a loping surf groove and a lazy shaker that suggests almost anything besides ecstatic fits of joy. And then the singer gets free. He lets loose a blood-curdling howl that immediately redlines the song and that’s probably still resounding in the Beninese city where it was recorded. It is a wild thing, a shriek of joy, truly an entrant in the hall of fame of great rock ’n’ roll screams. Move over, “Won’t Get Fooled Again.”

It’s such a powerful shout that it shakes you into realizing that it’s the first of its kind on this two-LP compilation of afro-funk from Benin. The modest yelp that caps the North African lullaby of Elias Akadiri and Sunny Black’s Band’s “L’enfance” notwithstanding, the contested screams here aren’t being laid down by the musicians; it’s that the musicians are competing to make the listener scream.

And there’s a lot to scream about on African Scream Contest 2, the sequel to the legendary 2008 compilation of the same name put together by ace crate-digger Sam Ben Redjeb, the former flight attendant behind the Analog Africa label. Like its older brother, 2 makes the case for the vitality and richness of the music scene in Benin, a country whose musical legacy is greatly overshadowed by its Nigerian neighbors to the east and, to a lesser degree, by Ghana to the west.

The sounds here are immediately familiar, but reveal unexpected complexities: Les Sympathics de Porto Novo kick things off with a zamrock-worthy lead guitar before segueing into a loose afrobeat pattern, l’Orchsetre El Rego spangles a stutter-stepping afro-cuban jam with tinny synths and soul-jazz organ, the Orchestre Poly-Rythmo de Cotonou play chanting Ghanaian disco from deep pocket grooves while the vocals shift into wispy calls-and-responses that sound more like Tuareg vocal melodies than the sounds typically associated with West Africa. It suggests that Benin’s musicians soaked up everything that came near them and then some, a kind of accidental melting pot of sound.

Not that this versatility should be all that surprising; the incredible variety of African records that have been reissued since the original Scream Contest long ago illuminated the level of interplay among the various music scenes of the region for Western listeners. But it’s a welcome reminder that that interplay wasn’t only happening in the cultural hubs of Accra and Lagos, that the contemporary sounds of Mali and Morocco were just as mobile as their West African counterparts, and, more than anything, that style isn’t the sole property of power centers; this music was being made and adored for its own sake long before anyone outside of Benin — let alone the United States — had ears for it.

All of which gives African Scream Contest 2 a sense of power all its own, one that’s made manifest on the comp’s second track. Ignace de Souza and the Melody Aces set “Asaw Fofor” rolling on a rockabilly groove. de Souza himself leads the band with all the smoothness of Cab Calloway or Nat King Cole, and the sax, rather than stab along to the song’s rhythm, sits back and waits, finally taking a long, warm solo before bowing out for the rest of the song. That sense of confidence, the willingness to luxuriate in a groove or a tone or a feeling without hurrying to an ending, animates all of the music here, and, maybe more than anything else, makes me wonder what was happening in Togo, and The Gambia, and Gabon, and everywhere else in African flyover country.

aquariumdrunkard

Labels:

...sampler

Sep 11, 2018

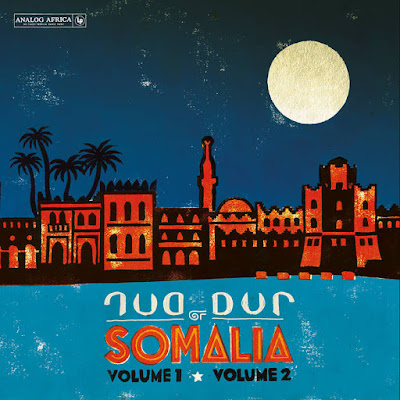

Dur Dur Band - Volume 1, Volume 2 & Previously Unreleased Tracks (by analog africa)

ollowing Analog Africa founder Samy Ben Redjeb's dangerous trip to Mogadishu in November of 2016, the label presents Dur Dur of Somalia: Volume 1, Volume 2 & Previously Unreleased Tracks. Dur-Dur, a young band from the '80s, climaxed as a band in April of 1987 with the release of Volume 2, their second album. The secrets to Dur-Dur's rapid success is inextricably linked to the vision of Isse Dahir, founder and keyboard player of the band. Isse's plan was to locate some of the most forward-thinking musicians of Mogadishu's buzzing scene and lure them into Dur-Dur. Ujeeri, the band's mercurial bass player was recruited from Somali jazz and drummer extraordinaire Handal previously played in Bakaka Band. Isse also added his two younger brothers to the line-up: Abukar Dahir Qassin was brought in to play lead guitar, and Ahmed Dahir Qassin was hired as a permanent sound engineer. On their first two albums, Volume 1 and Volume 2, three different singers traded lead-vocal duties back and forth. Shimaali, formerly of Bakaka Band, handled the Dhaanto songs, a Somalian rhythm from the northern part of the country that bears a striking resemblance to reggae; Sahra Dawo, a young female singer, had been recruited from Somalia's national orchestra, the Waaberi Band. Their third singer, the legendary Baastow, who had also been a vocalist with the Waaberi Band, and had been brought into Dur-Dur due to his deep knowledge of traditional Somali music, particularly Saar, a type of music intended to summon the spirits during religious rituals. From the very beginning, Dur-Dur's doctrine was the fusion of traditional Somali music with whatever rhythms would make people dance: funk, reggae, soul, disco, and new wave were mixed effortlessly with Banaadiri beats, Dhaanto, and spiritual Saar music. The concoction was explosive. It initially seemed that Dur-Dur's music had only been preserved as a series of murky tape dubs and YouTube videos, but after Samy arrived in Mogadishu he eventually got to the heart of Mogadishu's tape-copying network and ended up finding some of the band's fabled master tapes, long thought to have disappeared. This set reissues the band's first two albums -- the first installment in a three-part series dedicated to Dur-Dur Band -- representing the first fruit of Analog Africa's long labors to bring this extraordinary music to the wider world. Remastered from the best available audio sources. Includes two previously unreleased tracks; Accompanied by extensive liner notes, featuring interviews with original band members.

forcedexposure.com

- - -

A fantastic, hypnotic and funky compilation from the Dur-Dur Band of Somalia! This triple LP reissue of the band's first two albums -the first installment in a three-part series dedicated to Dur-Dur Band- represents the first fruit of Analog Africa's long labours to bring this extraordinary music to the wider world. Remastered from the best available audio sources, these songs have never sounded better. Some thirty years after they first made such a splash in the Mogadishu scene, they have been freed from the wobble and tape-hiss of second and third generation cassette dubs, to reveal a glorious mix of polychromatic organs, nightclub-ready rhythms and hauntingly soulful vocals. In addition to two previously unreleased tracks, the music is accompanied by extensive liner notes, featuring interviews with original band members, documenting a forgotten chapter of Somalia's cultural history. Before the upheaval in the 1990s that turned Somalia into a warzone, Mogadishu, the white pearl of the Indian Ocean, had been one of the jewels of eastern Africa, a modern paradise of culture and commerce. In the music of the Dur-Dur band -now widely available outside of Somalia- we can still catch a fleeting glimpse of that golden age.

clear-spot.nl

Labels:

Dur-Dur Band

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)