In 1997, a quiet, unassuming man of 59 years old named Victor Tavares -

better know as Bitori - walks into a studio for the very first time to

record a masterpiece which many Cabo Verdean consider to be the best

Funaná album ever made.

Bitori's musical adventure had begun long before this point. It was 1954

when he embarked on a journey across the seas to the island of Sao

Tomé & Principe. The young man's hope was to return to Cabo Verde

with an accordion.

Following two years of hard labour Bitori had succeeded in saving enough

money to acquire what was to become his most valued possession, his

cherished instrument. The two month journey back to Santiago, his island

of birth, proved time enough to master it. Self taught, Bitori

developed his own style, an infectious blaze, that quickly caught the

attention of the older generation. Before long Bitori was being asked to

share his musical talents, igniting the local festivities around Praia

with his music.

But not everybody welcomed the rural accordion-based sound. Perceived as

a symbol of the struggle for Cape Verdean independence and frowned upon

as music of uneducated peasants, Funaná was prohibited by the

Portuguese colonial rulers.

Performing it in public or in urban centres had serious consequences -

often jail time and torture awaited musicians that were “caught in the

act”. In light of such persecution the genre of Funaná began to slowly

disappear.

In 1975 Cabo Verde achieved independence from Portuguese colonial rule.

Along with Cabo Verde’s independence came a lifting of the ban placed on

Funaná. The musical repercussions in Cabo Verde were plenty - many

upcoming artists embraced Funaná, translating and adapting its musical

form in new ways. It was not to be until the mid-1990’s, however, that

Funaná in its traditional form was actually recorded.

It was a young singer from Tarafal, Chando Graciosa, who was to play a

key role in this event. Upon hearing Bitori, Graciosa immediately felt

drawn to Bitori's unique playing style - a raw and passionate sound

accompanied by honest lyrics that reflected the harsh reality of the

Cabo Verdean working class. He eagerly approached Bitori suggesting they

join forces and travel overseas with the objective of taking Funaná

beyond its rural roots. The two of them, with others in tow, achieved

their goal and travelled to Europe, introducing a receptive European

audience to the vibrant energy of Funaná. Eventually Bitori returned to

his beloved Cabo Verde. Graciosa opted to settle in Rotterdam in order

to pursue his career - he vowed, however, to bring Bitori across to

Holland at a later date to record an album.

In 1997 the time was ripe to immortalise the sound Bitori had shaped

over a time span of four decades. Built around a formidable rhythm

section, formed of drummer Grace Evora and bass player Danilo Tavares,

"Bitori Nha Bibinha" was recorded. The recording catapulted Chando

Graciosa to stardom, making him Cabo Verde's No.1 interpreter of

Funaná.

The success in Cabo Verde was phenomenal and Funaná rapidly gained the

recognition it deserved, especially in urban dance clubs. Bitori's songs

quickly became standards - classics known and loved throughout the

country. The musical success, however, was solely limited to the Cabo

Verdean islands - until now!

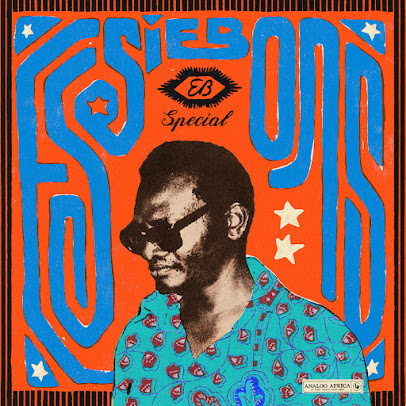

Analog Africa is proud to contribute to the worldwide promotion of Funaná - the once forbidden sound of the Cabo Verde archipelago - by releasing a worldwide re-issue of Bitori and Chando Graciosa's legendary recording.

- - - -

In 1998, Victor Tavares, known as Bitori, released an album of what is considered to be the very best Funana music to date, Bitori Nha Bibinha. Funana is a form of Cape Verdian music which was stigmatised as inferior by colonial society, despite being borne from it. Bitori spent an entire life playing and invigorating his beloved funana against the odds, with a gaita diatonic accordion; he recorded Bitori Nha Bibinha at 59. Analog Africa has re-released Bitori’s chef d’oeuvre as Legend of Funana, allowing old and new listeners to engage with Bitori’s grand moment of musical and postcolonial cultural triumph, once again.

Though this album was recorded in Rotterdam, its compositions take on the shape of mid/late 20th century Cape Verde. In every instrument we hear the spirit of women in headscarves at marketplaces, working to raise their families; open air conversations on rocky dirt roads amongst battered houses, and lookouts to a new horizon and ways out for a society during and after colonialism.

Bitori’s accordion playing is raw, humorous, lengthy, and aims to be magnificent. It has the sound of a passionate, romantic, existence. “Legend of Funana” is incredibly rhythmic and never once does its rhythmic section, comprised of drumming and bass, allow our attention to wander. The album’s first song is “Bitori Nha Bibinha,” the title of the song of this album’s first incarnation, Bitori Nha Bibinha. It is a song that asks its listener to dance. Every instrument aims to make a strong impression, though Bitori’s accordion is loudest.

It is an album of eight songs in total. The song “Natalia” mirrors the personality of a young woman, perhaps named Natalia. Language here is a barrier, but the song’s rhythm and raw accordion playing sounds surprisingly familiar, as if a portrait and landscape of the life of a young woman in a country where it is sunny, but there hasn’t been enough capitalist development to preoccupy a soul with professionalism and middle class rectitude. “Natalia’s” hand clapping is superb. “O Julinha” is a second song with a woman’s name, and this time the song seems to express the personality of a much quieter woman, to a ‘O, Julinha,’ that can only be a lament in any language. It’s a superb listen and a serenade that will warm the heart with its musical edge and rhythm anywhere in this world.This album’s vocalist is Chando Graciosa. His voice is strong, memorable, and sounds like that of a leader at a country fair or carnival: of large, communal activity. His singing style wows as much as the timbre of his voice; it sounds like that of a society passionately attempting to organise itself in the best way through communal culture. Miroca Paris, this album’s background vocals, is also phenomenal.

According to Britannica.com, a legend is a “traditional story or group of stories told by about a particular person or place.” Folktales, on the other hand, are not specifically about a particular person or a place that has existed or is still in existence. Like music, they allow our minds to run wild about the world around us by engaging our senses. A legend put to music should be doubly exciting then, if composed and performed to both legend and music. Tavares did not initially intend for his album to be a legend, but the fact that he is such a figure in Cape Verde’s music does make it so that the second title is appropriate – it is an album that engages as both a legend (that of a courageous and talented man who stood propelled indigenous culture) and as brilliant music.

- - - -

“Bitori Nha Bibina” is a joyous onslaught of accordion, metallic rhythms and call and response singing, led at the time of its 1997 recording by a 59-year-old man who had struggled awfully hard to be there. Bitori, in real life Victor Tavares, had made the 2300 plus mile trip from his native Cabo Verde to Sao Tome and Principe some 40 years before, seeking to earn enough money to buy the accordion he plays with such glee. Two years to buy the instrument, two more months to bring it home, Bitori accepted it all in order to learn the rural traditional style known as Funaná. At first he worked in the underground since the music was banned by colonial government, later, after independence in 1975, as celebration of Cabo Verde’s heritage, a blend of Portuguese and African influences.

his collection of songs, which features Bitori on accordion, the singer Chando Gracioso, Grace Evora on drums and Danilio Tavares on bass, catches him in exuberant form, layering short, repetitive riffs over swaying syncopations of drum, kit, cowbell and scratched and shaken percussion. The music is clearly meant for celebration, and you can hardly resist its call to sway and shimmy, yet there’s something melancholy, too, in the hoarse, emotive vocals and the slippery thrum of accordion. It’s an escape hatch, maybe, from the kind of world where two years hard labor might be seen as a fair trade for the axe that feeds your art, and where, famous many years later, you tour the world in your 70s, playing the scrappy songs of youth to people who have never been to your island nor will.

- - - -

20 years ago, Victor Tavares (aka Bitori) took his gaita- the diatonic accordion first brought to Cape Verde by the Portuguese- and laid down 8 tracks of smoking hot Funana grooves in a Rotterdam studio. The results ultimately rocked Santiago Island and the rest of the Cape Verde archipelago. And now those results, considered as good a recorded example of the style as any, driven by Bitori's accordion and underpinned by bass, percussion, and the constant metallic scrape of the ferrinhu, are seeing western release, leading to the always reluctant 79 year-old Bitori's decision to perform once again.

Funana is one of several rhythms specific to Santiago, and a musical style that was banned pre-independence, only becoming prominent in the late 1970s and 80s. It's likely modern, considering how many centuries ago the Portuguese first populated Cape Verde. So, like accordion and percussion-driven Cajun and creole music in Southwest Louisiana, ripsaw bands in Turks and Caicos, as well as similar styles in the Bahamas, this is 20th century stuff. Groove-wise, this record burns, and the rhythm section adds a buoyancy that lifts it from porches and streets and into clubs. Video of Bitori from 2016 onstage attests to the ability this music has to move asses. A listener with a sense of geography but no immediate sense of musical geography will hear the Caribbean. Or perhaps Mauritius and Reunion. It simply has the feel that comes from islands with colonial history and the imported, multi-cultural populations that get dragged to these places thanks to white people with endless amounts of arrogance and nerve. It's the sound of people who are themselves ethnic hybrids, snagging the instruments and even rhythms of the colonizers, marrying them with rhythms said colonizers would either ignore or do their best to banish. Yet, in the hands of people such as Bitori, who had to travel 8 days over the Atlantic Ocean from Santiago to Sao Tome and Principe so he could work for three years to acquire the savings to return home and buy a gaita, music becomes its own revolution. No wonder Funana is so infectious; it's been through hell.

Yet, long before Bitori finally recorded, something radical was happening to Funana, as well as other local grooves such as batuque and tabanka. Legend has it that a ship carrying what were in 1968 state of the art keyboard instruments from Baltimore harbor to Rio de Janeiro disappeared from radar and ended up on Sao Nicolau island, Cape Verde, where local folks marveled at this land-wrecked sight. The ship's contents were distributed to schools where there was electricity, so local kids could plug them in and immerse themselves in the magic Rhodes, Farfisas, Moogs, and Hammond organs might possess. The result, over the course of the next two decades, was an electric fusion, as the 2-beat funana groove got an update, and bands such as Os Apolos and Elisio and Voz de Cabo Verde gave the archipelago a then radical sound to compete with Haitian Kompas, Mauritian Sega, and French Caribbean Tumbele. In fact, this stuff not only rocked the entirety of Cape Verde, but founds it way back to Portugal as well as across the waters and into the Caribbean. One listen shows how organic this music's connection to the islands dotting the Americas is. There's the bristling disco of Fant Harvest's sung-in-English “That Day,” the synth-driven “Mino di Mama” by Quirino do Canto, and gaita player Joao Cirilo's decidedly psychedelic funana, “Po d'Terra.”

As is the case with Analogue Africa releases, tunes have been painstakingly distilled down to the cream, and both Space Echo and Bitori : Legend Of Funana have copious booklets with musical and geographic history, musician interviews, photos, and stories that truly bring the scenes to life. Of course, anyone who has decided that the two aforementioned releases aren't enough would do well to check out Ostinato records' sophomore release, Synthesize the Soul. This collection takes up where Space Echo leaves off, and features 18 tracks of classic, guitar and keyboard driven psychedelic funana. Yet, this is the music of the émigré, and as such, a number of the featured players here are from the Cape Verde diasporas in Paris, Rotterdam, Lisbon, and Boston, and so this collection does more than unlock a few more portentous dance tracks; it gives listeners one more historic hunk exposing how and why populations migrated and emphasizing how particular cultures have given the west its musical flair. In this case, infectious dance music from a chain of islands off the Senegalese coast made by people “harvested” from Europe and West Africa who had better things to do than serve their colonial overlords.