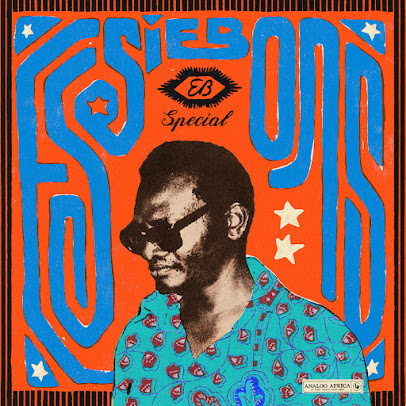

One of the most interesting tracks on Essiebons Special 1973–1984 Ghana Music Power House is Joe Meah’s mysterious "Dee Mmaa Pe". It’s not mentioned in the compilation’s accompanying booklet, and Joe Meah doesn’t figure in any of the standard discographies littering the world-wide web.

Despite this inscrutability, Essiebons Special’s second cut has a surprisingly familiar touchstone. Mainly instrumental with stabbing brass, a sax solo and odd vocal interjections it has a shuffling soul vibe. But the keyboard part dominates. What’s played nods so overtly to The Doors’s “Light my Fire” that it’s close-to certain Mr Meah or the keyboard-playing member of his band was paying keen attention to Ray Manzarek. This is the first release of “Dee Mmaa Pe".

The other thing known about "Dee Mmaa Pe" is that it is was recorded for Ghanaian producer Dick Essilfie-Bondzie, whose Dix and Essiebons labels achieved most success with highlife. C.K. Mann is the best-known name on Essiebons Special.

Essilfie-Bondzie, who died at age 90 last year, was integral to Ghana’s music. The booklet tells the story. He produced his first recording in 1959, then studied in London, returned home and became an employee of the Ghanaian government’s Industrial Development Corporation. He opened Record Manufacturers (Ghana) Limited, the country’s first record pressing plant in 1967. The Essiebons and Dix labels soon followed. In 1972, he left his government job. In 1978, he produced the film Roots to Fruits. As "Dee Mmaa Pe" makes clear, Essiebons Special looks at Essilfie-Bondzie from a new perspective. Six tracks are previously unissued.

There’s an emphasis on the funky, groove-based side of things. The C.K. Mann Big Band’s "Fa W‘akoma Ma Me" was originally included on the 1976 C.K. Mann Big Band album. Featuring some warm solo guitar (maybe from Ebo Taylor), it’s restrained and brings a Curtis Mayfield-esque viewpoint to highlife. "Wonnin a Bisa" by Black Masters Band (from a 1978 LP) is also grounded in highlife but, again, has this controlled feel. With at least these tracks, Essilfie-Bondzie defined a difference between the unconstrained live experience and what was released on record.

In contrast, Sea Boy’s "Africa" (from the 1976 album Across the Seas) feels as if it was taped at a live session. The just-about rocksteady rhythmic chassis is so direct it captures a moment which would not have lingered. Even though it’s a medley – so must have had forethought – Nyame Bekyere’s terrific "Medley (Broken Heart, Aunty Yaa, Omo Yaba (Nzema))" (from the 1976 album Broken Heart) has an analogous spontaneity.

Obviously, Essiebons Special 1973–1984 Ghana Music Power House doesn’t seek to be a definitive statement on Dick Essilfie-Bondzie and his labels. Instead, it emphasises that highlife has never been a musical straitjacket; that it could be the springing-off point from which any or many directions could be pursued. Which includes celebrating a fondness for “Light my Fire”.

- - - - -

“Highlife”, a name that stuck, was first used to reference the class divide of colonial Ghana. For many of the bands synonymous with this loose tag originally began playing to Europe’s upper echelons and civil servants, diplomatic classes at the stiffened ballrooms and tea dances. Many would also start out plying their trade as members of the various police and army marching bands. As trends, new musical styles emerged – from jazz to swing and eventually rock – these same groups began to shake off the prissy foxtrots for something altogether sunnier and dynamic.

Once Ghana (the first Sub-Saharan country to do so) gained independence in 1957 from Britain, the doors were truly flung open. This meant not only embracing the contemporary but the past too, as traditional beats, sounds and rhythms were merged with the new sounds hitting the airwaves from outside Africa. Highlife grabbed it all and much more. But if you really need a snappier summary of the phenomenon, it’s a merger of indigenous African sounds played with Western instruments. But then that leaves out the horns: a vital part of the overall sound originally brought in to replace the violin and strings. In that mostly lilted mix you’ll hear everything from calypso to Stax; funk to garage fuzz howlers. Of course cats like Fela Kuti, over on Nigeria, would turn-up it up, inject more political clout, rock and jazz to create Highlife’s offspring for a new age, Afrobeat – I’m well aware there will be arguments over that glib summary.

One of Highlife’s great impresarios is celebrated on this final Analog Africa compilation of 2021; a project prompted by the postponed (due to Covid) 90th birthday of the collection’s subject Dick Essilfire-Bondzie, who sadly passed away in August last year.

Though Ghana has found the spotlight before, with for example the brilliant Ghana Special box set from Soundway, no one’s put the emphasis on one of its chief instigators, movers and shakers, and the iconic label they set up: Essiebons. In a relatively thriving music scene, yet to be picked up by more than a couple of Western labels, in the 1960s Essilfire-Bondzie negotiated a deal with Philips which would change the scene forever with an enviable roster of acts and artists. Ghana could already boast of The Sweet Talks, Vis a Vis, The Cutlass Dance Band, T.O. Jazz and Hedzollah Soundz, but through the studio doors of Essiebons and its small offshoot Dix came the likes of legends like Rob, C.K. Mann, Gyedu Blay Ambolley and Ebo Taylor: many of which now appear in some form on this sixteen-track survey.

It was probably harder for Anlog’s label chief honcho and crate-digger Samy Ben Redjeb to decide what to leave out; although he’s actually unearthed six previously unreleased tracks from the archives alongside those that were released and made a splash. It’s not clear why this sextet was left in the vaults; it’s certainly not an issue of quality. Left dormant, funky little shufflers, saunters and gospel slumbers from Ernest Honny and Joe Meah get to excite the audience they never had.

It soon becomes apparent exactly what instrument the session player and band leader Honny excelled at, the organ being the focal point of all four of his turns screams, darts, stabs and flourishes. Honny had already put out the popular ‘Psychedelic Woman’ single with his Bees and appeared on various key and cult albums before going out alone on this quartet of performances. ‘Kofi Psych (Interlude I)’ the first of these is an organ showpiece that peppers, slams and dots notes and scales across an almost gospel-soul, bordering on the Bayou, backing. Herbie Hancock’s “wiggles” and squeeze box emitted buzzer meet on the sermon-like ‘Say The Truth’.

For his part, the relatively unknown Meah lays down an infectious Kuti-like funk groove on the smooth horn blasted and tooted ‘Dee Mmaa Pee’, and adopts synthesized effects on the relaxed tribal beat ‘Ahwene Pa Nkasa’.

Other fruits from the Essiebons tree include Santrofi-Ansa’s mid-tempo horn rasping and Curtis Mayfield crosses paths with The Meters and Issac Hayes crosstown jive talk ‘Shakabula’, and Seaboy’s familiar shuffled and lilted anthem prayer ‘Africa’. The alias of one Joseph Nwjozah Ebroni, who started out as a vocalist in the Bekyere Guitar Band (whose Across The Sea album classic featured Honny on organ duties), Seaboy also gets to side up once more with Nyame Bekyere for the soul-funk, telephone dial tone fluttered organ spot ‘Tinitini’.

It’s all good mind, with various adoptions of the Highlife gene, and some examples of technological advances as the label went into the late 70s and early 80s. And to think, if the late Essilfire-Bondzie had decided to stick with a career in business or the civil service (the whole background is laid out in the ever-brilliant, informative scene-setting liner notes), then Highlife would be without one of its greatest promoters and platforms. The label though was a great success; even venturing into film in the 70s with Roots To Fruits, a documentary exploring and featuring the titans of Ghanaian Highlife.

A golden period in the development of a sound that kept changing, adopting contemporary styles as it went on with a boom in recent years of modern Highlife, this compilation pays homage to one of its greatest champions. Analog Africa once more serves up a hot platter as the nights draw in closer and cold starts to bite. They finish the year on a high.

Wow.

ReplyDeleteGreat.

https://www.naijareporter.com

Sven speakers allow you to enjoy your favourite music with clear and powerful sound. The choice of speaker system significantly affects the overall listening experience.

ReplyDelete