Originally published by David Katz here!

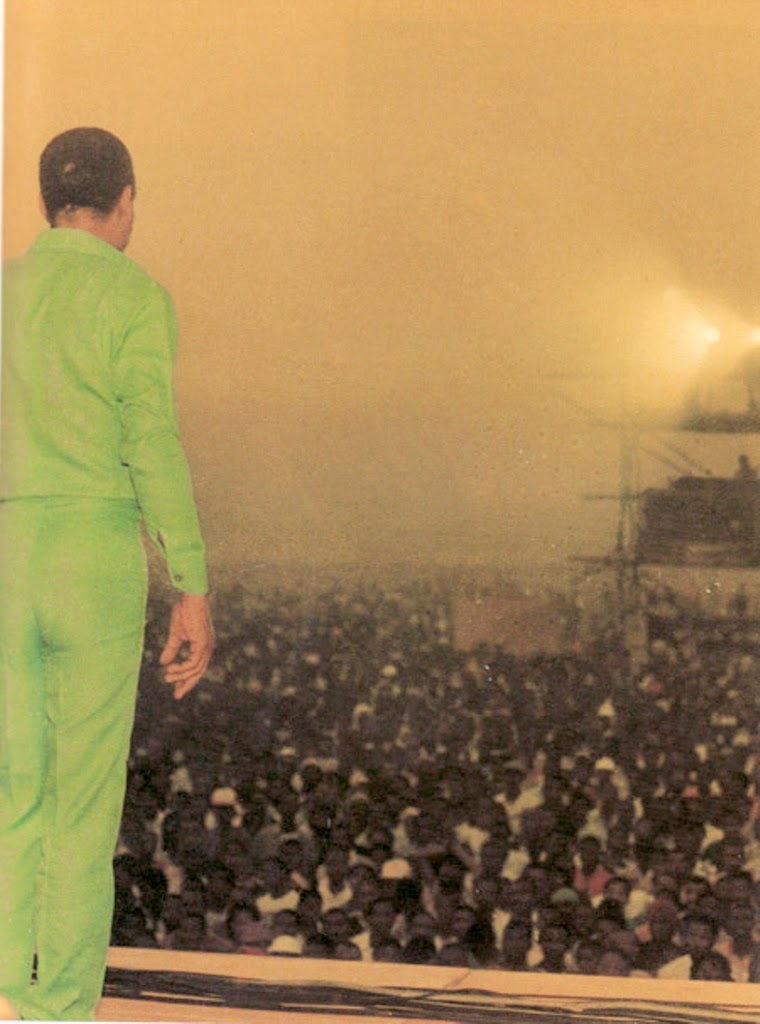

One of the most important musical and political figures to emerge in

post-independence Nigeria, Fela Kuti was the legendary rebel and agent

provocateur that pioneered afrobeat, an invigorating hybrid of dirty

funk and traditional African rhythms. A complex man that was equal parts

shaman, showman and trickster, whose perpetual criticism of Nigeria’s

governmental and religious figures made him a constant target, Fela was

one of a handful of exceptional individuals that forever changed our

musical landscape. What follows is a guide to his voluminous recorded

output, related as chronologically as possible.

Some of Fela’s earliest recordings, with the Koola Lobitos band, are featured on Lagos Baby: 1963-1969, but this is mostly fairly tame highlife, with early number “Onifere No 2”

and later soul-influenced tracks like “Abiora” holding only the barest

hint of what would follow. The bonus disc presents the band “Live At The

Afro-Spot” playing primarily jazzy highlife and blues. Unfortunately,

the sound quality is seriously lacking in places. For completists only.

The ’69 Los Angeles Sessions stem from Fela’s

sojourn in the City of Angels, and kicks off with the shape of things to

come in the near wordless “My Lady Frustration”, a gritty, funky number

that anticipates afrobeat, but the spectre of James Brown still hangs a

little heavy here. “Obe!” (“Soup!”) and “Ako” (“Braggart”) are more in

the mode of the standard afrobeat that would follow, and both

accordingly deal with social issues, while “Viva Nigeria”

is a surprisingly patriotic proto-rap inspired by the Biafran civil

war. In this transitional phase, you can hear that Fela is still finding

his way. Six songs recorded between 1964-68 are included as CD bonus

tracks, mastered from a far better source than on Lagos Baby.

Fela’s London Scene was cut in London at Abbey

Road, when Fela and his re-named Africa 70 band were on their way back

to Nigeria from the USA. Again, songs like “Who’re You” and “Buy Africa” are edging closer to afrobeat, but are still rooted in big-band jazz and less overtly political than future work.

By the time we reach the three-song Open And Close, we’re getting closer to full-blown afrobeat. The keyboard-led title track gives instruction for a provocative dance step, “Swegbe And Pako”

is a slow groove that decries incompetence in broken English, while

“Gbagada Gbagada Gbogodo Gbogodo” adapts a folk song that recounts a war

of liberation waged against the British. Fela’s keyboard playing is

distinctive here, but the afrobeat groove is not yet razor-sharp.

From the same era is the controversial Na Poi, a languorous track that was banned on release in Nigeria because it alluded too strongly to sex acts; B-side “You No Go Die… Unless”,

is a brass-laden, slowly swinging number in which Fela tells his

listeners in Yoruba that they will not face death unless they want to

die, despite Lagos’s many deadly perils.

The four-song concert album With Ginger Baker-Live!

features the equally volatile Cream drummer, who lived in Nigeria from

1970-76. Baker gets right into the groove, while Fela pokes at the

keyboards. “Black Man’s Cry” is James Brown-styled funk rock, with Fela crooning, “I am black and proud”

in Yoruba. “Ye Ye De Smell”, meaning “Bullshit Stinks”, was written

with Baker’s drumming style in mind, but is surprisingly melodic. Edging

further into afrobeat, but the overall sound is still largely

derivative of the JBs.

The real authentic sound of afrobeat as we know it truly begins with Shakara,

a groundbreaking two-song LP that first surfaced circa 1972. On “Lady”,

Fela explains that African females see the term ‘woman’ as a potential

insult; rejecting the Western notions of feminism, the song is a typical

Fela reversal. Its flipside, “Shakara”,

is also a total killer: its bright horn blasts frame Fela’s exploration

of the false bluffing that hallmarks Lagos’s domestic squabbles.

Roforofo Fight refers to senseless violence, describing two fools who batter themselves into the mud as a crowd gathers to watch them. The music sounds explosive,

with trumpet and saxophone paralleling the battle musically, as

afrobeat begins finding its way. Then, after a nine-minute instrumental

build-up, “Go Slow” describes the deadly crawl of Lagos’s perpetual

traffic jams. “Question Jam Answer” notes that hastily-asked questions

will inevitably draw an equally hasty response, while “Trouble Sleep

Yanga Wake Am” is an emotive creeper that warns of troubling the

troubled, since disturbing the disturbed can have dire consequences. The

musical arrangement is superb, with a melodious sax hinting at hidden

worries, an eerie vocal chorus heightening the unease.

Some say Afrodisiac was recorded during the London Scene

sessions, though it sounds like it was cut considerably later. “Alu Jon

Jonki Jon” is a driving number in which Fela hoarsely relates a

traditional Yoruba folk tale about a famine and a crafty dog. “Chop’n

Quench” (aka “Jeun Ko Ku”), a spirited instrumental, was Fela’s first

big hit, reportedly selling 200,000 copies. “Eko Ile” is another huskily

shouted number, singing the praises of Lagos in its original Yoruba

name, while “Je’Nwi Temi” (“Don’t Gag Me”) was one of the earliest songs

aimed directly at the authorities: against a disjointed guitar and

trumpet motif, Fela informs his governmental adversaries that he is not

going to shut his mouth, even if they jail him.

1973’s Gentleman is one of Fela’s first

statements decrying his countrymen’s colonial mindset. Following eight

minutes of distracted horn solos, Fela says in Pidgin that he is “Africa

Man Original”, rather than a ‘gentleman’ that seeks to ape the British –

powerful stuff.

Less inspired, but still holding attention, “Fefe Maa Efe” uses an

Ashanti proverb about women’s beauty as the launching pad for a tight

number in which Fela symbolically relates various topics in different

languages. “Igbe (Na Shit)” addresses the volatile nature of human

relationships.

As befitting its title, 1974’s Confusion starts with a troublingly empty electric piano, interspersed with echoing drums that don’t go anywhere. It takes five minutes for the bass to start,

but once the groove gets going, Tony Allen’s drumming percolates

superbly, and as more instruments join, everything becomes hypnotic.

Eventually, Fela discusses specific types of confusion that beset Africa

in the era of the post-colonial hangover. Later, he makes a complex

metaphor in which he compares Lagos to a corpse.

Alagbon Close refers to the centre of police investigations in Lagos, where Fela was often interrogated. Here, he reports what took place inside its walls,

backed by a chillingly sweet female chorus. The flipside, “I No Get Eye

For Back”, sung in Yoruba and Pidgin, reminds that we need eyes in the

back of our head, since so many always want to attack us.

1975’s He Miss Road also has a deceptively

pleasant feeling, but its playful lyrics mask a serious message –

particularly when Fela sings of a gorilla jumping onto a bus and the

inevitable pandemonium that follows. Then, the languorous “Monday Morning In Lagos”

feels much more tense, as Fela describes the inevitable comedown of a

broke Monday, following the squandering of cash on drinks during the

weekend. Similarly, the faster “It’s Not Possible” notes the

disingenuous false promises made by people who ultimately let us down.

Expensive Shit is another true landmark,

an excellent record of great political and musical importance. The

title track refers to a notorious incident, in which Fela swallowed his

marijuana stash during a search of his home, only to have his shit

searched for evidence, but not even a seed was found there. This is 13

minutes of sheer musical power, with the first six being particularly

tense and tight. “Water No Get Enemy” is equally enthralling, but is

driven by beautiful brass blasts, a lilting rhythm and full vocal

chorus, all of which salutes water’s great necessity.

Noise For Vendor Mouth is another long, tense song, in which Fela defends the good people of his alternative commune, known as the Kalakuta Republic,

who were branded thieves and weed addicts by the corrupt authorities.

Its despicable flipside, “Mattress”, compares women to a bed made

specifically for men to lie on. Fela’s defense? That men are essentially

polygamous by nature.

Everything Scatter is a wonderfully chaotic track

that attempts to portray the public’s contradictory views of Kalakuta.

The quick-action musical build-up launches directly into hectic jams,

punctuated by a wordless female chorus and compelling keyboard chops,

then moving on to fine sax soloing and expressive trumpet work. Then,

Fela describes the commotion on a public bus as it passes Kalakuta:

establishment types say the Republic has rabble, prostitutes and

thieves, but others say Kalakuta folk are honourable, their alternative

lifestyle commendable in a corrupt society. Fela then broadens the

metaphor to point out how conflict has kept Nigeria in a mess,

particularly under military rule. The flipside, “Who No Know Go Know”,

is even heavier: after a protracted build-up with keyboard noodling and

fearsome sax blasts, Fela bemoans Africa’s lack of unity, warning of

dire consequences.

Kalakuta Show was Fela’s dramatic response to

two notorious police raids that took place in 1974. The first saw Fela

charged with “possession of dangerous drugs” and “abduction of minors.”

With the case collapsing, the authorities raided the compound again,

breaking Fela’s arm and cracking his skull. But the tactics backfired:

the judge deemed Fela’s wounds unacceptable, and after his acquittal,

50,000 youths carried Fela back to Kalakuta. The song is 14 minutes of defiance:

Fela sounds completely enraged, yet full of wisdom. Flipside “Don’t

Make Garan Garan” is another slow creeper, this time with Fela railing

in Yoruba against self-centred egomaniacs that make life difficult for

the poor.

Unnecessary Begging begins with impressive sax work from Lekan Animashaun, before Fela delivers another complex metaphor,

explaining in Pidgin that begging is not needed in the ghetto, because

when someone lives by their word, they can gain their necessary rewards.

Then he widens the net to explain that in Nigeria, some make the

mistake of trusting the government to provide adequate facilities, but

the government says their mismanagement is a problem of fledgling

democracies – an idea as unnecessary as begging in the ghetto.

The mocking Ikoyi Blindness has Fela railing against the Lagos elite, who look down on ghetto dwellers whilst blindly aping colonial masters. Flipside “Gba Mi Leti Ki N’Dolowo“,

or “Slap Me Make I Get Money”, referenced recent lawsuits served by

poor Nigerians against influential figures. Both tracks cruise along at a

fair pace, and are engaging, if not quite essential.

Yellow Fever has a slow build-up with

keyboards giving way to horns, before Fela names various fevers that

affect mankind, including malaria, hay fever, influenza and jaundice, as

well as “freedom fever” and “inflation fever”, before moving on to

“yellow fever,” a condition of the mind that causes Africans to bleach

their skins – another killer, voiced atop a wicked groove. But the flipside revises “Na Poi”, which is more filler than killer.

1975’s semi-obscure Monkey Banana advances

with caution, the keyboards giving way to trumpet and sax (along with

fine conga work), before a ‘la-la-la’ chorus starts up and Fela begins

his diatribe against “book people,” warning the poor not to be

hoodwinked into a life of servitude by the propaganda of the rich. His

ultimate demand: “Give him the banana, straight…don’t make him work like a monkey!”

Flipside “Sense Wiseness” continues the attack, warning that foreign

degrees are meaningless if locals distance themselves from common

people.

Excuse O is an up-tempo groove in which Fela speaks of things our fellow men do to annoy us,

such as pilfering our beer, picking our pockets, trying to steal our

girlfriends… the obvious reaction is to shout, “Excuse, O!”, as in,

‘Excuse me! Let’s not quarrel, give me back my thing!’ Unusually, this

one has foreboding music but light-hearted lyrics. Flipside “Mr

Grammarticalogylisationalism Is The Boss” is a slower, meditative number

with surprisingly psychedelic keyboard scales, on which Fela decries

the Nigerian education system, and the fact that a better command of

English results in a higher salary. Delivered in strangely unbalanced

Pidgin, yet still holding powerfully mocking anger.

Upside Down is a compelling one-off cut with American muse Sandra Isidore,

during her 1976 Lagos visit, that contrasts the orderliness of the West

with the chaos of Africa. Fela wrote the track and Sandra tackles it

with verve, despite the Pidgin sounding peculiar in her mouth. On the

flip, Fela revisits “Go Slow” in a more abstract form.

Zombie is one of the most outstanding works of the period.

It starts off strong with a rousing horn fanfare that holds portents of

the important message he will deliver: the zombie of the title, who

does whatever he is told unthinkingly, is revealed to be a soldier of

the Nigerian Army. The song became a huge hit, but cost Fela dearly, as

it led to a thousand soldiers unleashing a brutal attack on Kalakuta in

February 1977, in which Fela was nearly killed, his wives raped and his

mother thrown out of a window. The record is simply superb – Fela firing

on all cylinders and the band at their prime. Original flipside “Mr

Follow Follow” is also thoroughly excellent: a powerful creeper in which

Fela warns listeners not to follow blindly – if one needs to follow at

all, it is best to follow with eyes and ears open! Some CD reissues also

include outtake “Observation Is No Crime”, another slow and

surprisingly playful track in which Fela proclaims in Pidgin that he

will not accept censure. There is also a live Berlin Jazz Festival bonus

track, “Mistake”, in which Fela differentiates between ‘good’ and ‘bad’

mistakes, calling on African leaders to acknowledge their errors.

1977’s Johnny Just Drop is billed as “Live from the Kalakuta Republic”, but credits indicate a studio recording. It begins with an extended bongo jam

before the bass kicks in, a sax solo starts and the song speeds up

considerably. After 13 minutes, an abstract female chorus joins, before

Fela describes the folly of “JJDs,” those Nigerians freshly returned

from overseas, whose way of being is anything but African. An obscure

number, initially issued with an instrumental mix on the flip.

True classic Sorrow, Tears And Blood has Fela at the peak of his powers,

another hard-hitting statement that directly addressed the horrendous

Feb ’77 raid (although it was also inspired by the June 1976 Soweto

Uprising). The song feels ominous from the get-go, with fine sax and

keyboard interplay before Fela emotively describes the attack, the

soldiers leaving their “regular trademark” of violence. Flipside

“Colonial Mentality” has another dramatic build-up, the horns nicely

counterbalanced by intricate percussion, and Fela himself on expressive

tenor sax, the lyrics again addressing the colonial mindset of Africans.

Opposite People zips along quickly, with brighter than usual Fela keyboard chops,

and rousing horn fanfares for ten minutes, before Fela explains that

“opposite people” will reveal themselves as a disruptive presence.

Flipside “Equalisation Of Trouser And Pant” sounds more foreboding, the

horns holding a sense of urgent discord and the percussion hinting at

unforeseen troubles; after ten minutes, Fela playfully uses trousers and

pants as a metaphor for class inequality.

Stalemate is another post-raid track concerned

with man’s inability to resolve conflict. The intro has some bum notes,

along with a strong sax melody, and the lyrics concern stalemates

forged by quarrelling women and untrusting hustlers. All very playful, considering the turbulent era in which it was cut.

Flipside “Don’t Worry About My Mouth O”, aka “African Message”, has a

heavier rhythm. Its symbolic message skates between playfulness and

seriousness. Fela says he will use a chewing stick to clean his teeth

and water to clean his ass instead of toilet paper, because this is the

African way, and points the listener to The Black Man And The Nile, instead of the Bible. A most peculiar outing, but still good.

Fear Not For Man begins with a tortured scream and a cough, before Fela delivers a drum-backed sermon on Kwame Nkrumah. An addictive funk groove follows,

leading to more shrieking and impressive conga lines. Flipside “Palm

Wine Sound” is a pleasant instrumental referencing the guitar style, but

here with added afrobeat emphasis.

Around the same time, Fela cut a new version of Why Blackman Dey Suffer,

a fearsome indictment of colonialism, again with Ginger Baker in tow

(it was first cut circa 1971, but deemed too radical). It starts with a

slow, portentous groove, swiftly invoking a traditional Yoruba chant.

Soon some floor-toms kick in as the keyboard improvisation becomes more

intense, offset by a rousing horn fanfare, in which baritone sax is

particularly resonant, leading to extended tenor soloing. Fela then

reminds that black folks are perpetually broke because Africa was raped

and pillaged; unity is the ultimate solution. The mix makes excellent

spatial placement of instruments, and stereo panning heightens the

effect of disjuncture – fiercely radical and expertly arranged. The CD

includes another misplaced track, “Ikoyi Mentality Versus Mushin

Mentality”, with another great stereo mix. Here Fela contrasts the

avarice of Lagos’s wealthy with the honest openness of ghetto folk.

After a delicious 11-minute build up, No Agreement

finds Fela almost professing the opposite of what we expect: he says he

will keep his mouth shut if speaking up is going to betray his fellow

Nigerians. The rhythm is fearsome with vibrant conga beats, the horn

section particularly tight, and there is a fine trumpet solo from Lester Bowie.

Flipside “Dog Eat Dog” is a moody, helter-skelter instrumental, leading

with oddball keyboards from Fela, and settling into an insistent stomp.

On 1978’s super-heavy Shuffering And Shmiling, after a long build-up, Fela launches an attack Christianity and Islam,

condemned as non-African imports from Rome, London and Mecca. His

intended targets were then-President Obasanjo, a Christian, and MKO

Abiola, an Islamic businessman that later ran the country, but he also

vents frustration with religious hypocrisy in general. Fela goes on to

describe the over-crammed public busses, full of poor workers

“shuffering and shmiling,” blinded by the promise of a better status in

the afterlife. For its original release in France, the B-side was

“Perambulator”, which starts with an odd bass solo, soon switching to a

rapid rhythm led by off-key keyboards, replaced by chaotic horn blasts

and percolating congas. Later, trumpet and sax solos lend a feeling of

seriousness, until Fela begins an odd rant about perambulators coming

and going – another symbolic look at the state of modern Africa, which

Fela says is stuck in a rut. Perambulator

finally surfaced in Nigeria in 1983, backed by “Frustration” – an

extended re-cut of ‘My Lady Frustration’ in fuller stereophonic form.

1978 was a very tumultuous year for Fela. After marrying 27 women, he

travelled to Ghana, but was expelled when a performance of “Zombie”

instigated a riot. That November, after Fela was heckled at the Berlin

Jazz Festival, much of his band ditched him, fearing he would pour the

profits into his campaign for the Nigerian presidency, following his

formation of a (disqualified) political party. But the following year,

another landmark recording surfaced: Unknown Soldier,

one of Fela’s most direct statements about the Kalakuta raid, which a

government report attributed to “unknown soldiers.” The 15-minute

introduction is heavily laden with ominous fear before Fela starts up

his sermon, recounting the horrible brutality that saw so many raped, a

student’s eye knocked out, and Fela’s 78-year-old mother sustain

injuries which ultimately killed her. Stevie Wonder gets a namecheck as

well. Over 30 minutes of ultra-powerful magic.

VIP (Vagabonds In Power) was the opening number from Fela’s controversial headlining of the 1978 Berlin Jazz Festival.

The 20-minute track begins with a rambling introduction in which Fela

informs the audience that 99% of what they hear about Africa is wrong.

He then reveals that the VIPs who abandon the poor are really “vagabonds

in power.” Later, the rhythm charges, the audience starts clapping

along and an emotive sax solo leads to full horn fanfares and percussive

breaks atop Tony Allen’s livid drum rolls. Fela eventually decries the

greedy VIPs and their evil ways.

Surfacing in 1979, ITT is another Fela killer straight to the head of corrupt leaders

and the cronies that prop them up, namely President Obasanjo and

corporate business whiz Mashood Abiola – then head of the Nigerian

branch of International Telephone and Telegraph, here re-cast as

“International Thief-Thief.” The song has urgency right from the start,

its wailing sax demanding notice as a cute chorus shrieks out the

“thief-thief” motif. Fela links the evil deeds of ITT to the legacy of

colonialism – strong words with a forceful rhythm behind them.

1980’s Authority Stealing continues the theme

of thievery in power, this time with a parallel drawn to the rough

justice meted out to petty thieves in the street markets, their crimes

linked to the reduced price of Nigerian oil. The band is totally tight here,

with super-fine soloing from the saxophonists (particularly Lekan

Animashaun), as well as trumpet blasts, wicked lead guitar and oddball

keyboards from Fela. A fine work, worthy of wider acknowledgement.

Half of Music Of Many Colours is Fela at his

most funky, helped by the looming presence of Roy Ayers, who toured

Nigeria with Fela in 1979. The original B-side, “2000 Blacks Got To Be Free”,

sees Ayers in fine form, banging out a fast-paced vibraphone line as he

implores Africans to unite. Ayers dominates this super-funky track, but

gets some three-dimensional embellishments with African percussion and

the chorus of Fela’s wives. The original A-side, “Africa Centre Of The

World”, feels much more afrobeat, yet has extra atmospheric brilliance

though Ayers’s chilling vibraphone. The horn parts are particularly

complex and resonant, and the chorus that chants the title sounds

magnificent, as Fela rejects the notion of Africa as the ‘Third World.’

Another absolute winner.

1981’s Coffin For Head Of State again returned

to the 1977 Kalakuta raid, which resulted in the death of Fela’s mother

in September 1979. Specifically, the track references the parading of a

symbolic coffin to the seat of government immediately after, delivered

as a gesture of defiant anger to then-president Obasanjo. The song holds

anxiety and tension in the off-kilter keyboards and vacillating horn

blasts, before Fela begins a lament about religious hypocrisy aimed at

corrupt leaders such as Obasanjo and his northern Muslim ally, Yar Adua

(who would become President in 2007), who both witnessed the coffin’s

delivery. Fela delivers his message in jester mode, but the seriousness

is not lost on the listener in this hefty track – serious and deep.

The understated Original Sufferhead, the first

album to name Fela’s band as Egypt 80, was released soon after yet

another brutal attack on Fela’s compound, in which he nearly met his

death. The title track starts off with an urgent pace and frightful keyboard sprints,

then forceful horns work up the tension and an odd ‘la-la’ chorus

presents a discordant diversion. After emotive soloing, Fela sings in

Pidgin about the non-availability of water, food, lighting and housing –

post-colonial problems that have turned Africans into “sufferheads,”

despite the continent’s many resources. B-side “Power Show” has a

complex, full-force arrangement that makes spectacular use of the horns,

Fela’s own tenor sax work sounding particularly strong. Then Fela

attacks obstructive immigration officers, money-grubbing postal workers

and egoistic generals that abuse their poor labourers just to exercise

power over another.

From here on, as Fela became more reclusive, his recorded studio output seriously slowed. Music Is The Weapon is a live album, recorded in Amsterdam in November 1983 and given a final mix-down by Fela and Dennis Bovell.

The chaotic concert featured Fela’s son Femi on alto sax and Dele

Soshimi on electric piano, along with four faithful wives and some

rising unknowns. “MOP” or “Movement Of The People” referenced the

political party Fela formed to contest the 1979 general elections. On

“You Give Me Shit I Give You Shit”, Fela ultimately calls for

tit-for-tat action; the slow groove has a long-winded tale about a

corrupt businessman, and future president Abiola is again targeted. The

final track, “Custom Check Point”, begins with frantic and discordant

keyboard work, leading to abstract female choruses. Fela’s subject this

time is the “scramble for Africa” that resulted in the continent’s

terrible division. A complicated work of several distinctive sections,

with some fine soprano sax soloing from Fela.

1985’s Army Arrangement is another complex creation

that looks at Nigeria’s neo-colonial situation. After searing horns and

distracted choruses, Fela starts his complex Pidgin sermon on

injustice, which is incongruously disrupted by ribald commentary. There

follows thoughts on the way that Nigeria’s military governments always

end up giving the reins back to the same politicians that were in power

before their coups – a highly contradictory situation – and reminds that

dissenting political parties such as Fela’s MOP are always obliterated;

all of which is dismissed as an “army arrangement,” a corrupt and

repressive double-dealing that results in death and destruction. Some CD

reissues also included the previously unreleased “Government Chicken

Boy”, revealed as those petty civil servants and media fools that

support Nigeria’s corrupt political system. The peculiar track, which

rides a pseudo-Latin rhythm, has a terribly muddy, cluttered mix –

perhaps it was unfinished.

Wally Badarou produced 1986’s Teacher Don’t Teach Me Nonsense, a high point of this sparse period,

making full use of the audio spectrum though a superb arrangement that

emphasises the brass through expert spatial placement. This time, Fela’s

message concerns the role of teachers, but he fears that after

schooling, the corrupt governments of post-colonial Africa become our

teacher; instead of democracy, Nigeria has “dem-all-crazy.” Therefore,

he surmises, if the former colonisers of Europe and the neo-colonial US

are meant to be Africa’s teachers, then please, don’t teach me no

nonsense! B-side (of overseas editions) “Look And Laugh” resembles a

melancholy highlife: in it, Fela attempts to explain why he had become

so reclusive, due largely to the brutal attacks by soldiers.

1989’s Beasts Of No Nation has many targets, being another great Fela diatribe,

despite some vocal weakness. This quietly meditative number starts with

fine musical interplay and some Yoruba choruses, before Fela appears as

“basket mouth” to deliver his message: he speaks of time spent in

prison on trumped-up charges, and references a campaign unleashed by the

military government led by General Buhari, known as the ‘war against

indiscipline’, in which the Nigerian public were deemed “stupid.” Fela

then speaks of the “animals in human skin,” such as Thatcher, Reagan,

Botha and Mobutu – the “Beasts Of No Nation” of the title. Overseas

issues also had the track “Just Like That” (issued in Nigeria as a

separate album with “MOPP”), a witty, funky ditty in which Fela says

that change can come swiftly in Africa – both positive and negative.

On 1989’s Overtake Don Overtake Overtake, a clavé-type cowbell leads the insistent rhythm.

Fela references past classics like “Kalakuta Show” and “Zombie”, moving

on to attack the military governments of Africa, which fail to liberate

the people. Musically, the second bass that appears late in the song

adds another layer of texture. Some US issues include the track Confusion Break Bone

(a separate LP in Nigeria), a slowly creeping update of “Confusion”.

After sax solos and a trippy conga break, Fela speaks of police,

military and governmental wrongdoings. Then, a weary Fela ultimately

says that the situation that turned Lagos into a corpse on “Confusion”

has now seen the corpse run over by traffic; hence the idea that

“confusion break bone.”

The final Fela studio album was 1992’s Underground System, a messy disc that evidences a chaotic frame of mind.

“Underground System” starts with a ghostly bass, adds throbbing

percussion and stabbing piano, then shrieking female choruses and horn

fanfares. Fela begins to chant in Yoruba, then speaks in garbled Pidgin

about trying to stop soldiers from ruining Africa. He praises Nkrumah

and curses “great African thieves,” like Obasanjo and Abiola. He says

the “underground system” that operates in Africa will always see a

leader like Nkrumah, Lumumba, Sekou Toure, Thomas Sankara or Idi Amin

killed off, while scoundrels will always force their way into office at

the expense of the people – evidence of the underground system at work.

B-side “Pansa Passa” is also chaotic: drums clash with wobbly piano,

then bass and guitars are met by a woodblock, and sax solos start, but

Fela says little, other than recalling the earlier defiant masterworks

he cut, such as “Alagbon Close” and “Monkey Banana”. The overall feeling

here is of weariness, rather than originality, which is perhaps

unsurprising, considering all he had gone through, his wariness of

harassment by the repressive regime of Sani Abacha, and the AIDS that

was already wreaking havoc with his immune system. In just a few short

years, Fela would make his final transition, leaving our physical plane

on August 2, 1997, aged 58.

Of the posthumous releases, there are two must-have DVDs: Music Is The Weapon (included in the Fela Kuti Anthology), a revealing documentary made largely in Nigeria by Stephane Tchal-Gadjieff and Jean Jacques Flori in 1983, and Teacher Don’t Teach Me Nonsense,

a BBC documentary from 1984 which has a sober interview, interspersed

with concert footage and bolstered by contextual scenes exploring

Nigeria’s recent history. Fela is also part of Konkombe: The Nigerian Pop Music Scene, from Jeremey Marre’s excellent Beats Of The Heart documentary series. Concert DVDs include Live at Glastonbury from 1984 and Live In Paris from 1981.

The first Fela book was the revealing This Bitch Of A Life

by Cuban ethnologist Carlos Moore, first printed in 1982 and recently

revised. It was adapted from the pair’s personal conversations, so there

is much ‘hip’ jargon, as well as firsthand testimony from wives and

Sandra Isidore. The most in-depth exploration of Fela’s life and work is

Fela: The Life And Times Of An African Musical Icon

by Michael Veal, an academic at Yale that spent a long time in Nigeria

conducting research, and even played for a time in Fela’s band. And

Steve McQueen is currently working a Fela bio-pic, so watch this space.

Viva Fela!

David Katz is an author, music journalist, DJ and reggae historian residing in the UK. He has previously written about the reggae scene in São Luís Do Maranhão, Brasil for the Academy web magazine.

No comments:

Post a Comment